This week we look at ALIENS, a terrific 80’s sci-fi war film. And a great sequel to a great movie. We get a chance to dive into sequels, how ALIENS uses several of the same story beats as ALIEN while still being a distinctive movie. The two films also give us a chance to examine the differences between 70’s and 80’s films, because while ALIEN has the gritty real-world feel of the 70’s, ALIENS is all 80’s action-blockbuster, complete with larger-than-life characters giving clever quips as they gun down monsters.

Here’s the links:

And here’s the script to the episode. (Note: this is not the transcript. This is the script I recorded from, but there were some changes and tweaks while recording and editing.)

Hi, I’m Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where every week we do a deep dive into a movie or TV episode. And to go along with this analysis, every week I publish a graph of the story we’re covering on the storylanes.com website, a graph I produced while doing the analysis. You don’t need to look at that graph – the podcast is standalone. But if you’re interested in diving a little deeper, check it out at storylanes.com.

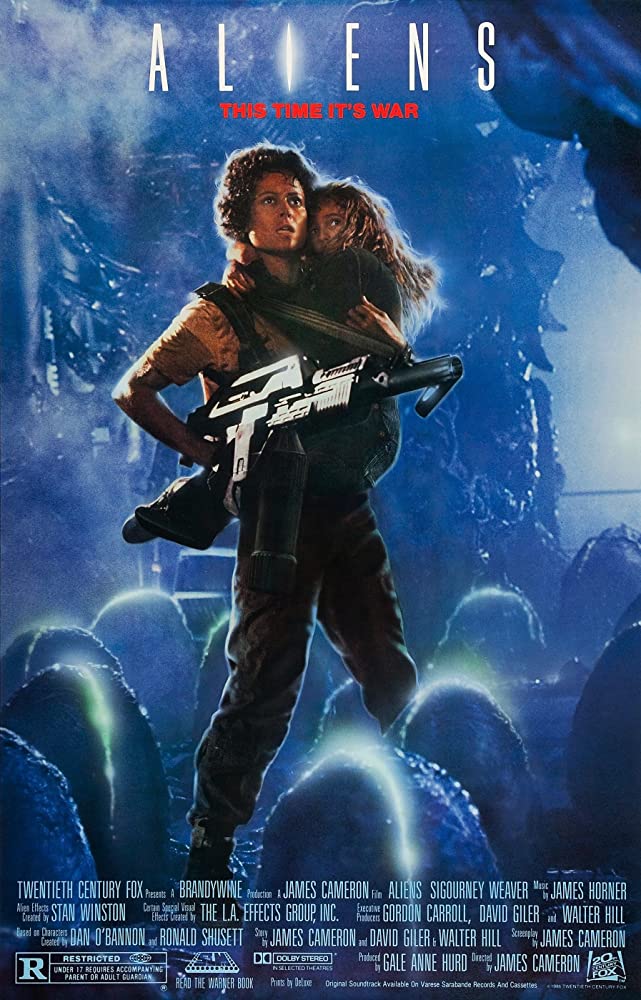

This week we’re doing ALIENS, the science fiction horror/war film that came out in 1986. Written and directed by James Cameron from a story by James Cameron, David Giler, and Walter Hill, and starring Sigourney Weaver, Carrie Henn, Michael Biehn, Paul Reiser, and Bill Paxton.

As usual, this podcast assumes you’ve seen the movie. There will be spoilers. And there won’t be detailed explanations of plot points. So if you listen to this without knowing the movie, you’re out of luck: the movie will be spoiled for you, and you may not understand what I’m talking about. It’s basically the worst of all worlds. So go watch ALIENS, if you haven’t. It’s terrific.

Perhaps the first thing to note about ALIENS is that it’s a sequel to ALIEN. So in that spirit, this episode is a sequel to the last one, where we covered ALIEN. I’m going to be talking a lot today about the relationship between the two movies. You don’t have to know ALIEN or listen to the last episode to appreciate this week’s podcast, but it would help.

ALIENS tells the story of what happens to Ripley after the events of ALIEN. When we last saw her, she was hibernating in a hypersleep capsule in the Nostromo’s lifeboat, on her way back to civilization after having defeated an alien monster. ALIENS starts with Ripley being discovered. She wakes up to a new world, fifty-seven years after she went to sleep, and the authorities don’t believe what happened to her. Until, of course, they discover that those pesky aliens are at it again. This time they’ve wiped out a colony, and Ripley has to go back with a squad of colonial marines to deal with the infestation. It all goes bad, most of the marines are killed, the company representative once again turns out to be a treacherous slimeball who almost kills Ripley, and Ripley once more has to single-handedly defeat an alien monster who has stowed away on her ship before she can go back into a sleep capsule and return home.

And oh, this time there’s a kid. Newt, the sole survivor of the colony wiped out by the aliens, which gives Ripley a chance to get her mom on.

So what makes this movie special, and why is it still worth talking about 35 years after it first hit theaters?

First off, ALIENS is a fascinating hybrid of genres. It’s a science fiction movie, sure. And a monster movie – we’ve got the aliens back, and as I noted last episode, I believe they are one of the greatest movie monsters around. This time around they even add a Queen, which only ups the cool factor. And there’s certainly some horror DNA in this film – hard to avoid, given that it’s a sequel to ALIEN, one of the greatest science fiction horror movies.

But at its heart, ALIENS is a small unit war movie. It’s the story of a small military unit that enters enemy-occupied territory, fights off enemy attacks, penetrates deep into the enemy base to recover an important McGuffin, and then gets out and gets home. It’s SAVING PRIVATE RYAN. It’s the DIRTY DOZEN. It’s the GUNS OF NAVARONE. Only now it’s in space.

And a brief bit of film jargon, for those who’ve never heard of a McGuffin. The McGuffin is the thing that everyone wants, the thing that makes the story work. This is a term used by Alfred Hitchcock to represent the item that drives the plot. In Hitchcock films, it can be microfilm, or a jar of uranium ore, or a suitcase full of money. It doesn’t really matter – and the audience doesn’t even have to know what it is for it to work as a plot device. What’s in that glowing briefcase in PULP FICTION? It’s a briefcase full of McGuffin!

In ALIENS, Newt becomes the McGuffin, the thing that drives Ripley to attack the Queen’s lair. And what a great McGuffin – she not only motivates Ripley’s heroism, but she lends thematic weight to a film that is ultimately about motherhood.

Before we dive deeper, let’s talk a moment about the tone of ALIENS. Because it makes a fascinating contrast with ALIEN.

ALIEN, remember, came out in 1979. This was the tail end of a golden age of movies, a decade that gave us such classics as THE GODFATHER, THE EXORCIST, TAXI DRIVER, and THE FRENCH CONNECTION. Among many many others.

ALIEN is very much a film of the 70’s. It’s got a gritty sense of realism, and the characters are flawed human beings doing their best to play the hand that life deals them. It’s about as real as you can get when the movie is about an alien monster attacking a spaceship.

That was, of course, keeping with the vibe of the 70’s. This was the age of American decline. Loss in Vietnam. Watergate. Stagflation. The hostage crisis.

But then the 70s ended and the 80s began. And now, Reagan was in the White House, and America began to swagger again. Suddenly, movies were bigger, with larger-than-life figures fighting vast forces for box-office gold, with more focus on entertainment and adventure and less on realistic views of day-to-day life.

And ALIENS is very much a film of the 80’s. The characters are all larger than in ALIEN. And a little more stereotyped. A badass marine shoots quips and bullets, a whining coward is more whining and cowardly – and entertaining – than you’d ever expect to meet in real life. Even the aliens are bigger and more numerous, with the huge Queen being bigger and more dangerous than the alien ever was.

But that’s okay, because Ripley is more of a badass too. While in ALIEN, she slipped on a spacesuit to just barely toss the alien out the airlock, in ALIENS, she improvises a suit of powered armor and gets in a slugging match with a giant Alien Queen.

Everything’s bigger and more bombastic. And a little more fun. Because it’s fun to hear Hudson whine, “Game over, man.” Certainly a lot more fun than hearing Parker and Brett grumble about the size of their share.

So with that in mind, and realizing that ALIENS is a small unit war movie, let’s meet the unit.

First, of course, is Ellen Ripley. Ripley’s our hero, a woman who was horribly traumatized by the events of ALIEN. A woman who doesn’t want to go anywhere near those monsters again. But she’s drawn in, against her will, by the fear that the aliens will be freed to run amuck across the galaxy. Because she’s that kind of hero, someone who wouldn’t turn her back on a risk like that.

And she’s competent. She’s constantly showing herself more together, more capable, more decisive, than the marines around her. When Lieutenant Gorman panics as his unit is being decimated, Ripley is the one who keeps her cool and drives the APC into the alien nest to rescue the survivors. When the squad is drastically reduced by its first contact with the aliens, it’s Ripley who says they should nuke the site from orbit. And when Newt is captured, it’s Ripley who launches a one-woman raid into the alien nest to rescue her.

It’s worth comparing the Ripley we see here to the Ripley we met in ALIEN. In ALIEN, you got the impression that Ripley was just a little more competent and cool-headed than the other crew members. She was the one who knew you shouldn’t let face-hugged Kane into the ship. She was the one who took the lead when the captain was killed. She was the one who survived.

But she didn’t seem that much better than the others. And while Ripley was certainly tough, she didn’t seem super-heroically tough.

In ALIENS, Ripley is better than everyone else in just about every way. She keeps her head when everyone else is panicking. Her plans are better than anyone else’s. When it comes time to load the shuttle, she’s better with the powered exoskeleton than the grunts doing the job. And by the end, she’s even a better marine than the marines as she launches her raid, complete with her assault rifle duct-taped to a flamethrower. She’s the ultimate badass, much larger than life, certainly larger than the Ripley we met in Alien.

Similarly, the rest of the folks along for the ride are bigger and badder than the crew in ALIEN. Where the Nostromo’s crew were a bunch of working class stiffs, the marine squad of the Sulaco is full of big-personality badasses with guns.

Apone is a tough-guy sergeant whose first act on waking is to stuff a cigar in his mouth. Vasquez is one tough lady who shoots down her fellow marines almost as effectively as she shoots down aliens. Bishop the android shows feats of superhuman speed with a knife for the entertainment of all, something we can’t imagine Ash, the android from ALIEN, doing. And while Ash was nefarious in subtle ways, the company traitor in ALIENS, Carter Burke, is an outright sleazeball from jump, a guy who can say of a decision that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of colonists, “It was a bad call.”

Perhaps the most entertaining of these characters is Hudson, who fluctuates between extreme bravado and comic cowardice in ways that, while not entirely realistic, never fail to entertain. His whines are some of the more entertaining and memorable lines in the movie. “I don’t know if you’re keeping up with current events, but we just got our asses kicked, pal!” “Game over, man!”

But to really see the difference between ALIEN and ALIENS, I think the best comparison could be between the leaders of these two crews. In ALIEN, Captain Dallas wasn’t the most competent leader in the world. He could be indecisive at times, and willing to follow rules even when doing so wasn’t the best idea in the world, as when he deferred to Ash in not disposing of the face-hugger. Though he would break rules in a short-term crisis, as when he ordered the crew to let the away team with face-hugged Kane back onto the ship. But overall, while not a super-heroic leader, he wasn’t bad – he didn’t panic when things got bad, and he was always willing to lead from the front.

By contrast, Lieutenant Gorman, leader of the marine squad, is completely useless. He doesn’t inspire his troops – they complain about him behind his back. He is almost completely inexperienced: when asked how many drops he’s been on, he answers, “Thirty-eight… simulated.” But only two actual combat drops – including this one. And his obvious fear when making that drop, well, it’s not what soldiers want to see from a man leading them into danger. And it’s far more terror than we can imagine ever seeing from Captain Dallas.

When things go bad, Gorman is even worse. In a state of terror, he starts spewing useless orders that provide more iconic lines. “Apone, I want you to lay down a suppressing fire with the incincerators and fall back by squads to the APC.” Which, in the context of everything falling apart as it hits the fan, is worse than useless: the orders distract Apone and get him killed.

Gorman does manage to redeem himself in the end with an act of sacrificial courage, but still. There is nothing subtle about this depiction of a man in over his head, a man who probably shouldn’t be in charge of the simplest operation, let alone this mess. We’re now in the world of 80’s films, and unlike the ALIEN of the 70’s, subtlety is not desired.

One last character to mention, and that’s Newt. A nice kid, a brave kid, a thoroughly traumatized kid. There’s not much else to her, though she does have a couple moments where she shows both courage and intelligence. She’s a good addition to this bunch.

So now that we have our characters in place, let’s take a look at the story structure.

The structure of ALIENS is a lot less clean than that of ALIEN. So I’m going to leave mapping it against standard story approaches until later and instead dive right into how I map the structure. Because hey, it’s my podcast, right?

I think ALIENS can be best broken into six acts. I’ll give a brief run-through of where I think the act lines fall, then go into more detail.

Act one sets up Ripley’s story. She gets back to Earth, but then agrees to go out Alien hunting.

Act two is a second round of setup. Call it setting up the marines’ story. We meet the marines. They land on the colony planet. They get some idea of the situation there and what’s happening. We meet Newt. But we don’t yet meet the aliens.

Act three is the first alien contact. It doesn’t go well. At the end of it, the marine squad is cut down so that we’re down to four marines plus four non-marines. And we know the aliens are coming soon.

Act four is the alien attack on the complex. By the end, we’re down to four survivors, but Newt is captured by the aliens and Hicks is wounded and out of action.

Act five is Ripley’s raid on the alien nest. No one dies except lots of aliens. And our heroes escape into space.

Except, of course, they’re not safe yet. So Act Six is Ripley’s battle with the Queen on the ship. She wins, everyone goes to sleep, the movie ends.

Now I’ll be the first to admit that figuring what counts is an act, and what is just a great big sequence within an act, is hard to define. So perhaps it’s time that I address the question of what I mean when I speak of an act. So my definition of an act is…

Well, it’s hard to say. It’s incredibly subjective. I’m doing this largely by gut feel about what are the major pieces of the movie.

But if I were to give a general rule of thumb, I’d say this: If you had to describe the plot of a movie in one paragraph, the acts would be the sentences. And if I were to describe ALIENS, I’d say something like this:

After Ripley wakes up, she has to go face the aliens again because they’ve attacked a colony planet. She goes back with a squad of marines, but when they get there they find only an empty base with no colonists except one little girl. They find that the colonists are in an atmospheric processing plant, but when they go there they’re attacked by aliens who kill most of the marines and destroy their landing craft. The aliens then attack and kill most of the surviving marines while capturing the little girl. When Ripley goes into the alien nest to rescue the girl, she meets and fights an Alien Queen. They get back to their ship in orbit, but the Queen hitches along and Ripley has to defeat her in epic single combat.

See, one sentence per act. Though admittedly, I’m probably cheating a little. Still, I do think the story breaks up that way. As I said, it’s all by gut and instinct.

Anyway, let’s dive a little deeper into those acts.

It’s interesting to me that there are, in effect, two acts worth of setup. We need to setup Ripley’s story, and that takes a full act with four major sequences. First, Ripley wakes up, finds she’s been asleep for 57 years, and has a nasty hallucination that establishes that she’s suffering some major PTSD from the events of ALIEN. And really, who can blame her?

In the next sequence, Ripley is put in front of a tribunal of skeptical suits who don’t believe her story about the alien attack. So they take away her crew license.

Next there’s a sequence on the colony planet that is in the script but was cut from the film. (Though they filmed it, and you can find it on some special edition releases of ALIENS.) In this sequence, we see someone sent out to investigate the alien spaceship from ALIEN. But as anyone who saw that film might guess, it doesn’t end well, with one of the investigators face-hugged.

Finally, in the last sequence of the act, Burke asks Ripley to go with him back to the colony planet to figure out what’s going on. At first she says no, but she eventually agrees. And so we’re done with this initial act. 17 pages and Ripley is off on her adventure.

So here, ignoring the scenes that were cut from the film, we have three nice clean sequences. Sequence one: Ripley comes home. Sequence two: nobody believes her. Sequence three: Ripley agrees to go back.

Next comes the second act, which I think of as the second act of setup. Although Ripley’s agreed to go on the mission, and her backstory is now established, we still know nothing about the other characters she’ll be with and what’s the situation on the colony planet. That’s the purpose of this act – to introduce all the other characters, and to start things out on the colony planet.

In the first sequence, Ripley and the marines wake up on the ship above the colony planet. And we meet the marines, all those folks that we’ll be spending the next hour and a half with.

We also get introduced to their toys, all those fancy guns that will be useful but not decisive. And, of course, we meet the powered exoskeleton that will become so important in act six.

In the next sequence, they land on the planet and the marines do the initial exploration of the complex. Nobody’s there, but there’s signs of a fight. So a big mystery.

And in the third sequence of this second act, they find a survivor. It’s Newt, the little girl who managed to survive the destruction of her entire colony, and Ripley bonds with her.

So note that again we have a nice clean set of three sequences. Sequence one: meet the marines. Sequence two: meet the planet. Sequence three: meet Newt. And now, with everything in place, it’s time to start the action.

Do note how this compares to ALIEN. ALIEN had only one act of setup, but it only needed one. We didn’t have an old friend that we had to catch up with, who we needed to get into the action. So there was nothing corresponding to ALIENS act one, where we largely catch up with Ripley and get her on her adventure.

But the act two of ALIENS is similar to the act one of ALIEN. We meet the crew. They land on a planet. They get an initial glimpse of what’s going on. No aliens yet, lots of setup. So there’s definitely similarities here between these two films.

And that act takes 26 pages, and we’re now on page 43. Again, not too different than ALIEN, where the setup act took 30 pages.

But now ALIENS comes to act three, and now things get real. Here there’s only two sequences.

In the first, the marines go into the atmosphere converter, meet the aliens, and get their asses kicked. This is one of the big action sequences of the film, full of close-in combat marked by chaos and confusion. And by the end of it, there are only six surviving marines: Hicks, Hudson, Vasquez, a knocked-out Gorman, and two pilots. On the civilian side, we have four: Ripley, Newt, Burke, and the android Bishop.

In the second sequence, our heroes have to decide what to do now. They agree to Ripley’s immortal suggestion: take off and nuke the site from orbit.

Only the aliens crash their landing ship, killing the two pilots. And now things are truly in the toilet, and act three is over.

We’re now a little more than halfway through the script, page 59 of a 105 page script. Act three took only 16 pages, but what an action-packed and consequential 16 pages it was. Now things are bad: our heroes are decimated, short of ammunition, with no way to get off the planet. And in act four, things will get even worse.

But not in the first sequence. In that sequence, the heroes return to the colony complex and fort up. They build barricades, block routes that the aliens might use to get in, and generally prepare. In a cut scene that shows up on some extended versions, they set out automated guns to kill aliens robotically. But we don’t see an alien – no dramatic action scenes happen here.

But it’s useful to have this quiet time. We’ve just come off a major action sequence, the first one in the movie, and the audience needs a moment to recharge.

That’s a good screenwriter note. ALIENS doesn’t go from action sequence to action sequence: there’s breaks, slow moments where things quiet down and the characters and the audience can breathe. This magnifies the impact when the action starts. So if you’re writing an action movie, add some quiet moments between the loud. Your audience will thank you.

After the initial forting up, things again get tense. This starts when we discover that the atmospheric processor suffered damage that’s going to cause it to blow up, taking the colony complex with it. We now have a timer running: our heroes have a fixed amount of time to get off the planet before the explosion. So Bishop heads off to do something that will help them get off planet.

And note that I don’t go into detail, because it’s not really important. The key thing is that Bishop is taken away from the group for a little while, he proves to Ripley that he’s a decent guy even if he is an android, and there is a way for them eventually to get off planet – it will just take a while.

In the final scene of this sequence, Hicks teaches Ripley how to use an assault rifle, knowledge that will soon be important to her.

Now it’s time for a little action, and for Burke to show his true treacherous colors. He does so by trying to infect Ripley and Newt with face-huggers. There’s a little action scene in which Ripley and Newt manage to keep off the face-huggers – just enough to wake up the audience and get them ready for what’s about to come. And, of course, Burke is revealed as truly horrible. He’s not just willing to sacrifice Ripley to get what he wants, he’ll even sacrifice a little girl, set her up for a terrible death. What a jerk!

And in the last sequence of this act, the aliens attack. It’s another big action sequence, and Gorman, Hudson, and Vasquez are all killed. As is Burke, but good riddance to him!

But the worst from our perspective: Newt is captured by the aliens, and Hicks is wounded and taken out of the action. So given that Bishop is needed to pilot the drop-ship, Ripley is on her own.

Act Four has taken 34 pages. It’s the longest act of the film. And now we’re on page 93, and things are looking grim.

And here comes act five, Ripley’s raid to save Newt. She goes into the atmospheric building, meets the Alien Queen, kills a whole lot of aliens, torches a whole lot of alien eggs, and gets out with Newt. The ship blasts off, narrowly avoiding being caught in the explosion of the atmospheric converter. And our heroes have gotten away, safe at last.

All of act five is one big action sequence, of course. We’ll get into that later.

Note also that this only covers 7 pages of the screenplay. Kind of short for an act, and there’s really only the one sequence. You might argue that this isn’t a full act, but instead only the first sequence of the final act. I’m not inclined to argue the point, except to note that I think that this feels like an act. If you were to give that one-paragraph synopsis of ALIENS, you’d certainly spare a whole sentence for Ripley’s raid on the alien nest. Ripley has to do a great big thing, a great big thing with great big consequences. So I call it an act, even if it is a short one.

Finally we’re back to the spaceship. And, of course, the alien Queen has stowed away. Ripley has one last big fight with the monster before spacing it, then everyone goes into a much-needed hypersleep rest.

So this is another action sequence and big fight. Though one notably unlike the other fights we’ve seen. This time, it’s Ripley vs the Queen, one-on-one. And it gets physical – it’s a fist fight, with Ripley in the powered exoskeleton to make her a match for the Queen. Quite different than all the firefights we’ve seen so far.

It’s a short act again – only 6 pages. Even shorter than act five. But I’ll still argue that it’s a separate act, that the two stand alone. They certainly feel like separate things when you watch the film.

There is one thing I want to note about this ending part, what I’m calling acts five and six. It is, in terms of the challenges that Ripley must face, remarkably similar to the final act of ALIEN, though made bigger.

Once more, Ripley is all alone. In ALIEN she was, at this point, the sole survivor. In ALIENS, the only other survivors are unavailable to help her. Hicks is wounded. Bishop is busy piloting. Newt is captured. So Ripley is on her own.

Once more, there’s a clock counting down to an explosion. In ALIEN, the clock was the Nostromo getting ready to self-destruct. In ALIENS, it’s the atmospheric converter getting ready to go boom. A bigger explosion that’s going to take down a bigger chunk of the universe.

Once more, Ripley goes into danger in order to save an innocent. In ALIEN, she goes back into the Nostromo to save Jones the cat. In ALIENS, she goes into the atmospheric converter to save Newt. And the stakes are definitely higher. Saving a cat is all well and good, but saving a kid? One as endearing as Newt? Yeah, that’s high stakes.

Once more, Ripley escapes to her ship, only to have to fight an alien. Only this time, she’s fighting a bigger alien, the Queen. And it’s a fist-fight, with Ripley in her exoskeleton. Again, bigger and badder.

And once more, at the end Ripley is in hypersleep on her way back to Earth. Only this time, the other survivors are in sleep with her.

So the basic beats are the same in the two movies, even though the changes keep it from feeling like a direct rip-off. It’s a good job, to do what was done before, but do it bigger and somehow keep it fresh. There’s a good lesson here in writing a sequel – you want to give the audience what they loved about the original, but somehow make it fresh. Cameron does a good job of that here.

So if, as I described last episode, I viewed ALIEN as having four acts, and I think ALIENS has six, why the additional acts?

First, we need two acts of setup here. We have to set up Ripley’s story, then we have to set up the group and the situation. In ALIEN, we didn’t need that first setup. If ALIENS didn’t have a defined hero from the start, we wouldn’t need to set up her story. So ALIEN, which doesn’t have a defined hero at the start, doesn’t need an act to set up her story. And thus one act of setup is enough for ALIEN, while ALIENS needs two.

Next, we turn to the end. Ripley’s returning to the Nostromo to rescue Jones didn’t feel like a big separate thing. It just didn’t feel like it rose to the level of a separate act. But her raid on the Queen’s nest does feel that big. The stakes are higher, the challenge bigger, the action more intense. So I think ALIENS ends with two acts, while ALIEN made do with one. As always, this is subjective. But that’s my read, and that’s why I think the ending required an additional act here.

So take it together and in my reading what was the single setup act in ALIEN became two setup acts in ALIENS, and the single climactic act of ALIEN became two climactic acts in ALIENS. Thus six acts instead of four.

It is worth comparing those other acts, though. What I call Act Two of ALIEN, everything from the face-hugger scene to the chest burster scene, maps to what I call act Three of ALIENS, the raid into the atmospheric converter where most of the marines are killed and the landing craft crashes. There’s clearly a whole lot more action in the ALIENS act. But the end results are the same: the crew is reduced in strength and now there’s a real threat.

Similarly, act three of ALIEN, the chest-burster scene until the moment when Ripley and the others decide to abandon ship, corresponds to act four of ALIENS, when the Aliens attack the complex and the survivors want only to abandon the planet without losing Newt. There is a structural similarity here. Both acts even include acts of corporate treachery: Ash in ALIEN, Burke in ALIENS.

So there’s definitely similarities in the structures, though they are different in scale, and there’s more of Ripley’s story that needs to be conveyed in ALIENS.

One thing I want to stress, though. I noted last episode that I was impressed with how clean the structure of ALIEN is. The structure of ALIENS is not as clean. But that doesn’t make it worse.

The structure of ALIEN felt right for that movie. The structure of ALIENS feels right for it. Structure needs to be the servant of story, not the other way around. Their different structures work for these different stories. Though it’s interesting to see their similarities, they don’t need to be identical.

Before we dive into subplots, I want to take a look at the action sequences of the film. ALIENS has five distinct action sequences. The raid on the atmospheric converter when most of the marines are killed. Ripley’s fight with the face-hugger. The alien attack on the base and the escape of Ripley, Hicks, and Newt from that attack. Ripley’s raid on the alien nest to rescue Newt. The fight at the end between Ripley and the alien.

All of these sequences are excellent. But there’s a couple other things worth noting about them.

First, they are all distinct and different. The raid on the converter is a large-scale action involving many humans with guns and flamethrowers, but the humans are the ones initiating the action and heading into enemy territory. There’s even a vehicle involved as Ripley drives in the APC. Then Ripley’s fight with the face-hugger is small in scale (though not small in stakes), primarily involving Ripley and Newt fighting two face-huggers. It is also mostly fought with improvised weapons – no guns here until the marines come in to finish things off. Then the alien attack on the base is another large-scale action with several humans, guns, and masses of aliens, but this time it’s in human territory. Ripley’s raid on the alien nest now has only one human fighter, deep in enemy territory, with guns. And finally the battle on the Sulaco is a no-guns fight between Ripley and the Queen set in human territory.

See all the differences, differences in the number of combatants, the territory where the battle is fought, the weapons used, the number and types of monsters involved. None of these battles are the same, they all stand out as distinct.

That’s an important lesson for screenwriters. Mix it up, don’t keep doing the same thing. The audience will enjoy different types of action, so give it to them.

The other thing to note about these sequences is how they are paced. The first one doesn’t start until page 47, almost halfway into this film. The second happens on page 77, another 30 pages in. After that, things accelerate: the third action sequence is on page 81, then page 95, then 100.

There’s definitely an accelerating pace here. While there are no action sequence for the first 47 pages of the script, there’s two in the last 10 pages.

So screenwriter note: pay attention to the pace of your action. And accelerate as the film goes on.

Now, let’s take a quick look through the subplots.

I found three major subplots. The first is Ripley as mother. This is an important subplot, because it also serves as the movie’s theme. It’s played out in both the way that Ripley becomes Newt’s mother and the way she battles the Alien Queen, another mother figure. In fact, the last two battles are between good mother Ripley and the bad mother Queen.

One interesting thing about this subplot is that its setup scene was cut from the film. The script has a scene where Ripley learns that over the 57 years that she was in deep sleep in the shuttle, her daughter grew old and died. Ripley did not get a chance to be a good mother for her daughter, a cloud that hangs over her throughout the film.

Or would, if they had kept that scene. But they cut it, apparently not thinking that it was necessary to setup the theme of Ripley as mother. And really, I tend to agree with them.

Because without that scene, this subplot works perfectly well. It starts when Ripley entices Newt to come out of hiding and join the group. Ripley’s kindness and motherly behavior towards Newt fills a void for this lonely child who has seen her own family killed by aliens. And slowly throughout the movie, Ripley becomes more and more of a mother to Newt. First by washing her face, then by putting her down to sleep, then by sleeping with her – all very normal mother behavior.

But this is an action-horror movie, so it can’t all be normal behavior. Ripley also rescues Newt from the face-hugger, something outside the usual motherhood experience.

Ripley goes even deeper into the realm of badass super-mom when she returns to the alien nest to rescue Newt from certain face-huggerdom. In doing so, she fights and defeats the dark mother, the Alien Queen. And while she does so, she torches all of the alien’s eggs – in effect killing the Queen’s children.

It’s worth noting that to pursue Ripley, the queen tears herself free from her egg-laying tubes. She would rather have revenge than more children, truly the act of a dark mother.

In the final battle, the Queen goes after Newt in her hiding place. Here Ripley gets to have a truly iconic moment when she emerges in her exoskeleton and issues that immortal battle-cry: “Get away from her, you bitch!”

Finally, the dark mother is dispatched. And here we have the climax of this plot, when Newt clings to Ripley and calls her “Mommy.” Ripley has truly earned her motherhood now.

And so, she tucks Newt into her hypersleep bed with reassuring words about bad dreams. The last image of the film is the two of them side by side asleep in their capsules. Not only is the subplot resolved, but the entire movie has become about the theme of motherhood and of the contrast between the loving protective Ripley and the vengeful destructive evil Queen.

The next subplot is the story of Evil Burke, and why you should never trust the corporation in an aliens movie. This parallel’s the Ash subplot in ALIEN, in which someone who we think is an okay guy turns out to be evil. Though Burke is not an android as Ash was – he’s just a venal creep who will do anything for his percentage.

This subplot starts early in the film, when Burke is the first person to really talk to Ripley after she has emerged from sleep. He then organizes the trip to the colony planet, ostensibly to check out the colonists but really because Burke believes there’s a profit to be made. Sure, Burke promises Ripley that they’re going to destroy the aliens. But it’s a lie.

Later, when Ripley proposes to deal with the aliens by nuking the site from orbit, Burke objects. He claims that it’s because the complex is so expensive, but we know better!

He presses more and more to bring the aliens back, reveling his true nature to Ripley in a scene on page 67. And later, he tries to let face-huggers infect Ripley and Newt – an unforgivable act, working against both the heroine and the small child. Burke’s treachery is now revealed to the team, and when the aliens swarm the complex, he tries to flee, blocking the path out for everyone else. But of course he’s caught by an alien, and dragged off to a much deserved fate.

There’s a scene in the script that didn’t make it into the movie in which Ripey later encounters a cocooned Burke in the alien nest. It’s clear that he has an egg implanted in him, and Ripley shows him mercy by giving him a grenade to kill himself rather than be chest-burst. But they cut the scene from the film, and really, it’s not needed.

One thing to note about this plot: it’s another case where the structure of ALIENS parallels that of ALIEN. In both cases, there is a member of the team who is a treacherous company man. In both cases, his treachery surfaces somewhere in the latter half of the film. In both cases that treachery leads to a tense scene when Ripley’s life is in danger. And in both cases the traitor is disposed of before proceeding with the major conflicts at the end of the film.

Another subplot is Bishop’s earning of Ripley’s respect. After her experience with Ash, when Ripley finds that there’s an android on board the Sulaco, she’s understandably upset. And so she rejects Bishop.

But when Bishop offers to crawl through the access tunnel to get to the comms uplink tower to try to bring down the other landing craft, he earns Ripley’s respect. And when he picks her up after the raid on the alien nest and the two return to the ship, he earns her affection. She tells him, “You did okay, Bishop.” Not exactly generous with the praise, our Ripley, but still, there’s some acknowledgment there.

Of course, that’s when the Alien Queen appears and tears Bishop apart. But even as only an upper torso, Bishop still saves Newt from being blown out the airlock, again earning Ripley’s esteem.

The final subplot that I noted was another character arc, that of Lieutenant Gorman. As I said before, Gorman is pretty useless throughout this film. But when he recovers from being knocked out, he is gracious enough to apologize to Ripley, even though she cuts him off. And at the end, when Vasquez is wounded so badly that she can’t flee the oncoming aliens, Gorman stays behind with her. The two blow themselves up, along with a bunch of aliens. But in that moment, Vasquez acknowledges Gorman by giving him her special handshake, the one she only shares with people she regards as her comrades. Gorman has earned his place in the marine pantheon with his heroic death, and Vasquez is the one to recognize it. Nice stuff – I’m always a sucker for a good redemption arc.

Now let’s look at ALIENS through the image of some standard screenwriting models. If you don’t remember these models, you might want to listen to the introductory episode of this podcast, where I describe the models that I’ll be discussing. You can find that on you favorite podcast service, or on the storylanes.com website.

The first of these screenwriting models is three act structure.

I’ve already noted that I think ALIENS has six acts. But it can be forced into traditional three-act structure without too much difficulty.

It’s a little uncertain where the inciting incident is in this script, however. In some ways, the inciting incident is when Ripley’s lifeboat is recovered at the start of the film. That’s what really starts the ball rolling – it lets Burke know there’s potentially valuable aliens out there, inspires him to order the colonists to check them out, which leads the colony to be destroyed by the aliens. And of course it leads to the mission to find out what happened and thus the bulk of the film.

If we take that as the inciting incident, that means that the inciting incident happens in the first scene of this film. Which certainly is not standard for any screenplay model.

But there’s another possible inciting incident. Here we look at things from Ripley’s perspective and say that the inciting incident is when she is asked to go on the mission to the colony world. This is the thing that upends Ripley’s life, such as it is. Though really, her status quo has barely been established – she just got back. But established or not, her life is turned upside down by Burke’s invitation to join the mission.

In either case, it’s pretty clear that, from a three-act perspective, act one ends when Ripley decides to go on the mission. And act two begins in the spaceship when Ripley and the marines wake from their long cold sleep.

So what’s the midpoint? A reminder: in traditional three-act structure, the midpoint is a major turning point when things get truly serious. It’s where the shit hits the fan.

I think the clearest midpoint would probably be when the drop-ship is destroyed by aliens, leaving our heroes marooned on the colony planet. They’ve lost their massive firepower and most of the marines, they have no way to escape, and there are aliens coming soon. Things have certainly gotten real. This happens at page 58, a little late for a 106 page script, but not too bad.

Another possible midpoint would be just a few pages earlier, around page 50. Here is when the aliens appear in the atmosphere converter and wipe out most of the marines. In one short scene, the marines have gone from in-charge with massive firepower to almost wiped out, fleeing for their lives and barely escaping. Again, things have gotten real – though not as real as they’ll get in just a few pages.

Act two continues until after the aliens have wiped out the fortress in the colony’s headquarters. We’re down to three adults, they’ve got a ship to get off planet, but the aliens have taken Newt. This is the moment when Ripley makes her decision and her plan and commits to it – she’s going in to rescue Newt. There’s no turning back now.

And act three, of course, is the two epic battles with the Alien Queen. The first in her nest, the second in the spaceship. And the climax, the moment when Ripley has blown the queen into space and Newt calls her Mommy.

So three-act structure works, more or less. I just think that ALIENS makes more sense if you regard it as being in six acts.

How does ALIENS shape up against Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat?

Well, pretty good, actually. First, all the things we noted for three-act structure apply here, because Snyder was basically expanding on three-act structure.

But look at the statement of Theme, which Snyder has on page 5. That’s actually pretty good – essentially, the statement of theme happens on page 6 of the script, when Ripley learns that her daughter died of old age, thus setting up the theme of motherhood.

There’s only one problem. That scene was cut from the film. So while there’s a statement of theme in the script, there isn’t one in the movie.

Beyond that, Save the Cat does pretty good. The page numbers are often off by a few, and here again the debate section, in which the protagonist wrestles with whether or not to go on the adventure, only lasts a page or two and not the 13 pages that Snyder calls for.

And while there is an all-is-lost moment when the aliens have captured Newt, there really isn’t much of a dark night of the soul. Ripley never despairs at losing Newt – she just starts arming up.

Ripley does have a moment when she sees the Queen laying her eggs and feels overwhelmed. Ripley gets pretty scared then, though only for an instant. Not quite a dark night of the soul. But maybe a dark instant of the soul.

The last thing I should note re Save the Cat: this is a film that actually has a fairly good pairing of opening and closing images. While it isn’t quite the opening image of the film, in the first scene we see Ripley lying alone in a hypersleep capsule, about as alone as a person can be. And the last image is Ripley and Newt in adjacent hypersleep capsules. Ripley is no longer alone – she is a mother now. Which is a pretty powerful representation of the key change in this film, full of thematic resonance. In other words, exactly what Snyder describes when he talks of opening and closing images.

The Hero’s Journey model also does pretty well. Again, this is not surprising: there’s huge similarities between these three screenwriting models. But ALIENS adheres closer to the Hero’s Journey than any of the films we’ve looked at so far. Ripley does refuse the call to adventure, though that refusal lasts less than a scene. And she has a mentor – the first mentor we’ve seen in these films. In this case, her mentor is Hicks, who teaches her how to use an assault rifle and generally how to be a badass marine. Hicks is even taken out before she has to face her biggest ordeal, something we expect of mentors. He appears a little later than the mentor typically appears, but not that far off.

It’s also worth noting that the Hero Journey’s equivalent to the inciting incident, the Call to Adventure, is more clear here than in the other models. That’s because the Hero’s Journey makes it clear that the Call to Adventure is all about the hero, so we can ignore the various incidents that start the action rolling and focus on the moment when Ripley gets the call. This is, of course, when Burke invites Ripley on the mission, an explicit call to adventure that Ripley first refuses.

To make some of the Hero’s Journey analysis work, you have to realize that Ripley’s goal is to become a good mother. So the moment when she approaches the goal is the moment that her relationship with Newt solidifies. And the later challenges she overcomes are, from this perspective, mainly obstacles to her being a good mother to Newt. Which makes sense – it’s hard to be a good mother if your child becomes an alien incubator, and that’s what Ripley is fighting to stop.

Even at the end, the Hero’s Journey works quite well. The Ordeal is Ripley facing the Queen in her nest. The challenge on the Road Back is the Queen stowing away aboard the ship. And the resurrection is the final defeat of the Queen.

Finally, the Hero has returned with the prize when, after blowing the Queen out the airlock, Newt calls Ripley “Mommy.”

We’ve covered a lot of territory. The last thing I really want to look at is one last comparison of ALIENS to ALIEN. Because I think ALIENS is a fascinating sequel. It is clearly in the vein of its predecessor, and as I’ve noted there’s major pieces of the structure that parallel the original. The basic story structure. The treachery of the company man. The challenges in the last act.

But ALIENS is a vastly different movie from ALIEN. While ALIEN was science-fiction horror, ALIENS is a war movie. There’s still chills, but they are more action movie chills than the horror movie chills of ALIEN. There’s nothing here quite like the chest-burster scene. And even when beats are similar, in ALIENS they are less horror. A good example of this is Burke’s treachery, which mirrors Ash’s treachery in ALIEN. But Ash is revealed to be an inhuman monster, and the images of him spewing white blood, and the interrogation of his disembodied head, are clearly horror-movie moments. By contrast, Burke is just a venal human whose treachery is more in the war-movie style. In other words, Ash is an inhuman monster, but Burke is just scum.

And there’s all those 70’s vs 80’s things I mentioned earlier, another key difference between these films.

The end result is, while ALIENS is clearly a valid sequel to ALIEN, it’s a much different movie.

And, I think, a terrific movie. It’s endlessly entertaining. The characters are marvelous. The creature design loses something from the fact that we’ve seen it before, but the Queen is still new and cool. There’s a solid theme here as well, something that was largely missing from ALIEN. ALIENS is about something, motherhood. ALIEN was just about the scares.

All in all, I think ALIENS may be a perfect sequel, owing a lot to its predecessor but with a fresh take. Well done, Mr Cameron!

So which alien movie do I like more?

Probably ALIENS. It’s a lot more fun. There’s more quotable lines. The characters are more fun to watch.

But there’s no single scene in ALIENS that is anywhere near as scary, effective, and memorable as the chest-burster scene from ALIEN. Probably not even anything that matches the face-hugger scene. And ALIEN is believable in a way that ALIENS is not – though that’s not necessarily an indicator of quality.

Do I see any problems in ALIENS? Nothing major. Hudson is such a memorable character, I would have liked to see him get a more memorable death. And there are a few inconsistencies between ALIEN and ALIENS. If the company knew there was something on that planet, as they clearly did in ALIEN, why did it take them 57 years to send someone else to check it out? How exactly do you build a colony and not notice the giant alien spaceship just over the next hill?

But I don’t have any major problems with any of this. For my real problems with the series, you’d have to look to ALIENS 3. But you’ll have to look at it without me. I saw it once, but never again. They lost me when they killed Newt at the beginning of the film, thus completely undercutting ALIENS, a film that I think is much superior in every way.

And finally, we get to the screenwriters lessons learned. What are the biggest takeaways from ALIENS?

First, sequels have to be the same but different. That’s hard. But look at the way ALIENS does it – it uses a lot of the story beats and complications from ALIEN, but it does it bigger, with a different tone. The same, but different.

Second, mix up those action sequences. Don’t repeat yourself – every action sequence should be different.

And third, timing your action sequences is crucial. They should probably come at an accelerating pace throughout the film. You can make what will be remembered as an action-packed movie with no action in the first half as long as you’ve got plenty at the end.

And that’s what I’ve got on ALIENS, and that brings me to the end of this week’s episode. As always, I hope you’ve enjoyed listening to this as much as I’ve enjoyed making it. And I hope you’ve learned something interesting about this film and gotten some ideas of the secret of a great sequel. Original, but still faithful to the predecessor. And if you’re a screenwriter, I hope you’ve learned something here that you can use.

In any event, check us out at Storylanes.com. There you’ll find a link to the script I worked from, along with the Storylanes analysis that shows the structure in more detail than I presented here. Well, different detail, anyway.

So I’ll talk at you next time. I’m not sure what movie I’ll be covering. Probably something a little more recent, and maybe not a classic that will last through the decades. For our purposes, all movies are worth examining, not just the great ones. But I haven’t decided for certain what I’ll be looking at yet. So yay, a surprise coming!

This is Joe Dzikiewicz for the storylanes podcast, signing out. Check us out at storylanes.com.