This week we’re looking at JOJO RABBIT, the historic drama/farce that’s all about a boy and his Hitler. This one is interesting: it allows us to talk about a new screenwriting model, the Mazin/LeFauvre method. As such, the links include links to fuller explanations of those methods.

And here’s the links!

- The script.

- The Storylanes analysis.

- Craig Mazin’s explanation of his method.

- Meg LeFauvre’s explanation of the method.

- Listen to the episode right here.

And here’s the script of the episode.

Hi, I’m Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where every episode we do a deep dive into a movie or TV show. And to go along with this analysis, I publish a chart of the story we’re covering on the storylanes.com website, a chart I produced while preparing the episode. You don’t need to look at that chart – the podcast is standalone. But if you’re interested in diving a little deeper, check it out at storylanes.com.

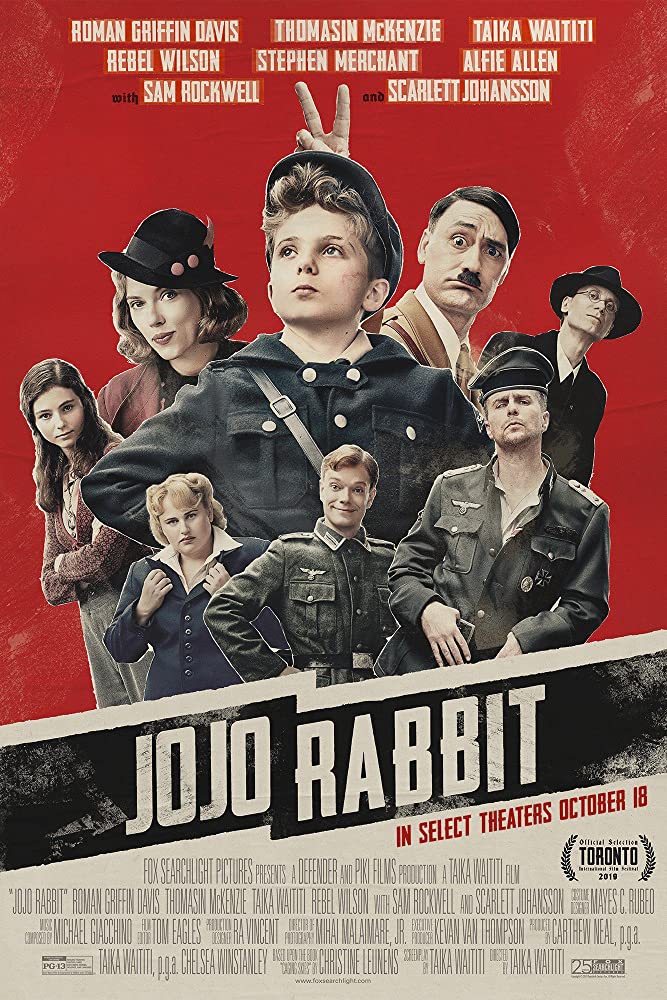

This week we’re doing JOJO RABBIT, the 2019 tragicomedy written and directed by Taika Waititi and starring Roman Griffin Davis, Thomasin McKenzie, Scarlett Johansson, Taika Waititi, and Sam Rockwell. It also won an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, so let’s see what an Oscar winner looks like.

As usual, this podcast assumes you’ve seen the movie. There will be spoilers. And there won’t be detailed explanations of plot points. So if you listen to this without knowing the movie, you’re out of luck: the movie will be spoiled for you, and you may not understand what I’m talking about. It’s basically the worst of all worlds. So go watch JOJO RABBIT if you want to listen to this podcast. I love this one, and it’s going to give us a chance to talk about a whole new theory of screenwriting structure. So go watch it and then come back and we’ll talk.

JOJO RABBIT is the story of Jojo Bentzler, a young boy growing up in the last days of Nazi Germany. Jojo is devoted to the Nazi cause, so much so that his imaginary friend is Adolf Hitler. But Jojo has his devotion tested when he finds a Jewish girl hiding in the walls of his house, a girl that Jojo’s mother is keeping safe. And in the end, Jojo learns empathy, choosing humanity and his growing love for the girl over being a Nazi.

The film is an argument for tolerance against bigotry, and for the simple quiet heroism that sometimes requires. Because there’s a cost to tolerance in this film, and Jojo’s mother pays it. In fact, there’s two major examples of sacrifice in the cause of decency in this film.

But one of the most interesting things about this film is its tone. Which in some ways is all over the map. The movie is at various times a farce, a tragedy, a drama about wartime life in a totalitarian state, and a sweet coming-of-age story about first love. The way it manages to pull off these switches of tone is a great example for the screenwriter, and worthy of study.

I’ve added a Tone lane to the Storylanes analysis that discusses changes in tone at any particular scene. I’ll also discuss tonal shifts as we talk about the structure of this film.

One particular thing to note about the tone is the way Nazis are portrayed in this film. They are always presented as farcical, even when they are frightening. And, ultimately, the Nazis are the primary source of both the absurdity and the tragedy of this film.

There are four main representatives of Nazism in this film.

The first is Jojo’s imaginary friend, Adolf Hitler. Adolf is a terrific comic invention. He’s a version of Hitler who references many of Hitler’s views, but generally doing it with an overblown comic sense.

Note his exaggerated discussion of Jews as monsters. His requests that Jojo “Heil me.” His absurdist twists on Nazi logic. His references to how he survived the bomb plot assassination attempt. It’s all delightfully over-the-top. And while there’s some real darkness underneath, it generally stays buried. (Though later in the film, as Jojo starts moving away from Nazism, Adolf gets darker in his anger.)

Also note: this is not the real Hitler – it’s Jojo’s imaginary version of him. The script calls him Adolf to help keep the distinction clear. I’ll be following that convention here.

Next is Captain K. He’s a German army officer who clearly has lost his enthusiasm for the cause. But even so, he’s over-the-top and absurd. Just note the ridiculous uniform he wears when the battle finally comes, complete with gold trim, makeup, and a flowing red cape. He’s definitely a comic figure, one who doesn’t take Nazism too seriously. But he’s also the only one of these Nazis who shows any humanity, at various times saving both Elsa and Jojo. In fact, he ultimately sacrifices his life for Jojo. He obviously doesn’t believe the Nazi nonsense he’s spewing, which leaves room in him for humanity.

Captain K is fascinating to me for another reason. He’s both a German officer and a decent human being, even a heroic one. There’s not many cinematic examples of that combination.

The next Nazi exemplar is Fraulein Rahm. She’s the ultra-enthusiastic supporter of Nazis. Another absurd character who is constantly saying ridiculous things. “It has been scientifically proven that Aryans are 1000 times more advanced and civilized than any other race. Now, get your things together kids, it’s time to burn some books.” And suitably, we last see her firing a comically oversized gun while running toward the enemy.

The last and darkest model are the Gestapo agents who come to search Jojo’s house. They are led by a tall skeletal figure all in black, the frightening Captain Deertz. These guys radiate a real sense of menace: if they figure out that Elsa is Jewish, it would be curtains for both Elsa and Jojo.

But still, they are presented as largely comic characters. Their signature action is the repeated Heil Hitlers, in which every time a new person arrives on the scene, everyone present has to Heil each other. It’s farcical in a way that calls out some of the more absurd aspects of Nazism.

So the Nazis are all ridiculous sources of absurdist comedy, the major source of the absurdist tone of this film. And yet, while the characters and their ideology are clearly ridiculous, the consequences of their presence is not. The most striking example is the bodies hanging in the town square, supporters of the resistance hanged for their actions. And, of course, Rosie’s body when it hangs there in the darkest moment of this film.

This is the tragic consequence of Nazism. But interestingly, the movie doesn’t show the Gestapo actually arresting or hanging any of these people. It certainly doesn’t show us Rosie’s arrest and execution. It would be hard, probably impossible, to show that and maintain the farcical presentation of the Nazis.

So that’s interesting: the Nazis provide this film with both farce and tragedy. The movie tells us that this hateful ideology is absurd while also saying that it’s deeply dangerous. It’s a fine line that this film manages to walk.

Well, in talking about tone, we seem to have stumbled our way into discussing characters. We’ve covered the Nazis. Now let’s look at the others.

First, there’s Jojo. Jojo is the protagonist, but he’s also the pivot of this movie. And the thing that is ultimately at stake here is Jojo’s soul.

Even when he is deeply wrong about Nazis, he is endearing. He’s a sweet kid who can’t quite live up to the horrible ideology that he adopts. He shows this at a couple of key moments.

First, when at the Hitler Youth Camp he is called on to kill a rabbit. This is where his Nazi beliefs are first tested. And it turns out he’s not willing to act on them.

This is a key moment in the film, the first time that Jojo chooses humanity over being a Nazi. It’s followed by other examples that we’ll get to later.

In any event, Jojo is a thoroughly endearing child, and we can see the decency at his core. We want to see this kid do well, and we want to see him choose a life of empathy and kindness instead of become a Nazi. He’s a great character to take us on this journey.

And this is crucial. Because almost every scene in this film is from Jojo’s point of view. We’re with Jojo for almost every minute, so it helps that we like him.

And perhaps some of the reason that all of the Nazis seem so absurd is that we’re seeing them through the eyes of a ten-year-old boy.

In the few exceptions to Jojo’s strict POV, we see the movie through the eyes of Elsa. There are a few scenes between Elsa and Rosie, and later there’s a couple moments in a montage where Elsa is the only character present.

Elsa is interesting, in that she’s initially presented as an antagonist for Jojo, but ultimately becomes his ally. And his unrequited love interest. She’s a fierce young girl, full of fire and courage. But also vulnerable at the core. She is a tough antagonist to Jojo, repeatedly disarming him. But she is hurt when he throws her boyfriend Nathan in her face. And later, she is bold enough to face the Gestapo and pretend to be Jojo’s sister, but terrified almost to the point of shock later when she realizes how close she came to being discovered.

So she’s both admirably tough, but also believable, with a raft of pain and fear that she tries to hide.

Of course, she also serves as the ultimate test of Jojo’s Nazi beliefs. And a test that, I’m happy to report, he fails. Or his beliefs fail, anyway – I suppose Jojo’s humanity ultimately passes that test.

Another key figure in Jojo’s test is Rosie, his mother. Rosie is another strong courageous woman. Jojo’s Mama Lion – and she acts it, as when she knees Captain K in the groin for letting Jojo get hurt. (And we should note, Captain K does not in any way retaliate. And it doesn’t keep him from later saying that “I’m sorry about Rosie. She was a good person. An actual good person.”)

That’s about as good a description of Rosie as one could hope for. She is, in fact, Jojo’s model for what it means to be a good person. She is anti-Nazi, though careful to keep it under wraps. Well, somewhat careful – ultimately, perhaps, not careful enough.

She radiates decency and love for Jojo. But even that love never causes her to lose her humanity. For her, a key moment is when she talks to Elsa, telling Elsa that if it comes down to it, Rosie will choose Jojo over Elsa. But even then, she can’t bring herself to truly threaten Elsa.

ROSIE: If I have to choose between you and my son… I won’t know where to send you.

Rosie’s death is, of course, the great tragedy of the film. And it’s particularly sad that she never gets to learn of Jojo’s growing decency, his ultimate rejection of being a Nazi. She’d like that.

The last character to note is Yorki, Jojo’s friend and confidant. Yorki is the other kid in the movie. He goes through much of what Jojo goes through. But Yorki actually gets though the Hitler Youth Camp and gets to be a child soldier. He kind of gets the character arc that Jojo wants at the beginning.

But Yorki lacks Jojo’s fanaticism. He is a model of common sense, as in this exchange with Jojo:

JOJO (CONT’D)

Hey Yorki… I caught a Jew. A real one.

YORKI

Wow, good for you! I saw some that they caught hiding in the forest last month. Personally I didn’t see what all the fuss was about. They weren’t at all scary and seemed kind of normal. But don’t tell anyone I said that.

And he’s capable to seeing the contradictions in Nazism, as when he says, “Our only friends are the Japanese and just between you and me, they don’t look very Aryan.”

He does try to be a good soldier, but he’s not really a good Nazi. And when the chips are down, he abandons his uniform. So all in all, a figure of common sense in a strange time. And a good friend to Jojo.

So, now we know our characters, let’s dive into the structure of this film.

JOJO RABBIT is another film that fits fairly well into three-act structure. In this, it matches several of the films we’ve looked at, films like ALIEN, GET OUT, and IT FOLLOWS.

And if you’ve been listening to this podcast, you know what that means. It means that I think of it as having four acts, with the midpoint breaking what three-act structure would call the second act into two distinct acts.

If you want to hear my argument for that, and you want to know about the other screenplay structures we’ll be discussing here, listen to episode one of this podcast. That’s where I lay out how I think about structure and describe the structure models that I reference here.

So what’s the one paragraph summary of JOJO RABBIT that can show us the structure of this film? I’d say it’s something like this.

Young Jojo is an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth. When he discovers a Jewish girl hiding out in his house, at first he treats her as a terrifying enemy. But he gradually falls in love with her and protects her from the authorities. Because of her, when the allies take over his town, he rejects being a Nazi and learns empathy.

So, four sentences, four acts. With the key story being Jojo’s coming of age and rejecting his Nazi views. Setup. Jojo fights with Elsa. Jojo falls in love with Elsa. Resolution.

The first act is all setup. We meet Jojo, see the Nazi world in which he lives, and meet his imaginary friend, Adolf Hitler.

It starts with an initial sequence of Jojo getting a pep talk from Adolf. The introduction of Absurd Adolf is a great way into the world of this film, and a great way to meet Jojo and establish his starting point as an enthusiastic Nazi. And it’s entertaining as hell – it draws us into this film.

For those who cannot accept the premise of comic Nazis, this opening provides a warning. If you can’t laugh at absurd Adolf, you won’t like this film. Might as well give up now.

In the next sequence we go to the Hitler Youth Camp. Jojo is at first enthusiastic about all the Nazi stuff, not noticing the darkness at the core. But when he gets the first test of his humanity, he passes by not killing the rabbit.

The rabbit scene is the first serious scene in this film. There is darkness under the other Youth Camp scenes. Antisemitism. Book burning. But the rabbit scene isn’t at all funny, it’s just grim.

And it shows the stakes of this movie. They are life-or-death. Because even though Jojo won’t kill the rabbit, the counselor does.

This is a fairly bold move. Jojo’s failure establishes that there will be consequences in this film. The victories will not come easy.

This is immediately followed by a scene between Jojo and Adolf. And Adolf is a source of humor and farce. He cheers up Jojo, and soon the two are dashing comically through the woods.

Of course, that leads to Jojo blowing himself up with the grenade. Which certainly surprised me. But even that is treated as comic.

The grenade is the inciting incident of this film. Jojo’s wounds take him off the Nazi youth track, the track that Yorki follows. He does not become a child soldier. And he is kept at home, out of school, which leads to his finding Elsa in the wall. The explosion shatters his status quo and sends him off on another path, just what we want from an inciting incident.

After the Hitler Youth Camp, there is a sequence where we introduce Jojo’s post-camp life. We meet his mother. We see Jojo at his new job working for Captain K and the Hitler Youth Office. And we see the ultimate stakes of this film when we see the bodies hanging in the town square. Although there have been hints of the darkness underlying Nazism before this, most notably in the rabbit scene and the other scenes of casual sadism at the Youth Camp, this is where we see the bared horrors of this world.

This is the first major tonal shift in the film. Although there were some dark overtones in the rabbit scene, it wasn’t too far off farce. But here, things get real. This is the first truly tragic scene in the film.

With that, we’re done with the first act. All the pieces are in play, and the story is about to begin.

This is a solid setup act. We’ve met most of the major characters. We’ve setup Jojo’s status quo, then sent him off on another path. And we’ve introduced both the farcical and the tragic tones of this film. All the pieces are in place – it’s time to start things rolling.

So now we’re into act two. To my mind, the heart of this act is Jojo’s battle with Elsa, ending when Jojo first shows some empathy for her.

In the first sequence, Jojo meets Elsa. Because of his injuries, he’s home alone from school. And because of that, he hears Elsa upstairs and discovers her hiding place.

He reacts like any child raised with Nazi propaganda would react, with fear and hatred for the Jew. He tries to fight her, but Elsa, older and tougher, quickly overcomes him and takes away his symbolic Nazi knife. So this sequence is, basically, Jojo and Elsa clash, Jojo loses. And the comedy here is rather broad. Not as broad as the Nazi scenes, but Elsa’s victory over Jojo is definitely played for laughs.

Though when Rosie comes home, she carries realism with her. In her scenes with both Jojo and Elsa, Rosie has humor, but she’s also a kind-hearted presence who takes the movie into sweet coming-of-age territory.

In the next sequence, Jojo reaches a truce with Elsa. He first visits Captain K and gets the idea of writing a book about Jews. This gives him a reason to work with Elsa, to do research. Of course, she makes up silly things for him, but Jojo believes them. And more importantly, it gives him a chance to work with her instead of fighting her.

There’s comedy here, but a more believable comedy. Except, of course, when Adolf comes out, because at this point in the film he’s still a reliable source of farce.

But the heart of the sequence is Jojo’s truce. He is no longer in open warfare with Elsa, but they’re not friends either.

Then, in the last sequence in this act, Jojo reopens his fight with Elsa. And this time, he manages to hurt her. He writes a fake letter, supposedly from her boyfriend Nathan. And it’s a cruel letter, and hearing it hurts Elsa. Jojo has won the battle.

Except he feels guilt for hurting her. He doesn’t have the heart to be cruel to Elsa. It’s like the rabbit scene – Jojo has too much empathy to feel good about his victory, to press forward and kill his prey.

And so he writes another letter from Nathan, a nice one where he rolls back his former cruelty. He shows his first signs of empathy with Elsa, and the sequence and act end with Jojo and Elsa arguing about Germans and Jews, but this time it’s more a gentle debate between friends than a real conflict.

This is the midpoint of the film. And it comes at page 48 of a 91 page script, so at just about the middle. Jojo’s worldview is starting to shift. And the playful conflict with Elsa is going to become something more serious as Jojo will soon have to fight bigger battles against more cruel antagonists.

It’s worth viewing this moment from Elsa’s point of view. Elsa clearly knows that Jojo’s letters are fakes. But they still hurt. Nathan is a sore spot.

And she recognizes Jojo’s kindness when he writes the second letter. She clearly knows what’s going on. It’s nicely done – we see this through Jojo’s point of view, and Jojo doesn’t realize that Elsa knows the letters are fake. But the audience knows it.

Now we have the moment when my quixotic battle with three-act structure rears its ugly head. Three-act structure would say that now, after the midpoint, we’re going into the second half of act two, when the fun-and-games period is over and things get serious. By contrast, this is where I say we move into act three, where the stakes are higher, the conflict gets bigger, and the tone is more serious.

Feel free to call this what you will. Ultimately, this is a pointless philosophical argument.

But hey, there’s nothing I like more than a pointless philosophical argument. So if you want to argue for three-act structure, bring it on!

But I’m going to stick to my guns and call the next section act three. But if you want to think of it as the second half of act two, I promise, I won’t get upset.

So, act three. I’d call this act, “Jojo falls in love.”

It starts with a sequence where Jojo falls in love with Elsa. This sequence starts when Jojo gets input from the key figures in his life. First is Rosie and she describes for Jojo what it means to be in love.

ROSIE

There’s always time for romance, babe. One day you‘ll meet someone special.

JOJO

Why does everyone keep telling me that?

ROSIE

Who else tells you?

JOJO

Everyone. Anyway, it’s a stupid idea.

ROSIE

You’re stupid. Love is the strongest thing in the world.

JOJO

I think you’ll find that metal is the strongest thing in the world, followed closely by dynamite and then muscles. Besides, I wouldn’t even know it if I saw it.

ROSIE

Surprise, surprise, your shoelaces are undone. Again. (she ties his laces) You’ll know it when it happens. You’ll feel it. A pain.

JOJO

In my arse I bet.

ROSIE

Nope, in your tummy. And your heart. Like butterflies. It’s like you’re full of butterflies.

Then he has separate scenes with Elsa, Adolf, Captain K, and Yorki. In various ways, from each of them he gets advice about his relationship with Elsa. It’s a nice way to get different points of view on where he is in his voyage. And certainly something a screenwriter should note – it’s nice to check in with all the characters right after the midpoint.

Finally, Jojo gives a gift of colored pencils to Elsa. And in doing so, he realizes that he loves her. Butterflies and all.

There’s a couple of other important things that happen in this sequence. There’s a nice scene between Elsa and Rosie. Here Rosie acts as Elsa’s mentor and talks with her about living one’s life with courage. And also, about being in love once again, there’s a focus on love. And once again, Rosie acts as a mentor, this time to Elsa.

The other key thing that happens is that Jojo sees Rosie distributing anti-Nazi literature. We’ve known for some time that Rosie is anti-Nazi. Now we see her at it. And not being too careful about who sees her – Rosie doesn’t notice Jojo noticing her.

But at the end of this sequence, Jojo now realizes he loves Elsa. Now it’s time for him to prove it.

Cue the Gestapo. Because they arrive at Jojo’s house, and he has to protect Elsa.

Or they have to protect each other. And what follows is a sequence full of menace, but still with humor, where the Gestapo search Jojo’s house, Elsa pretends to be Jojo’s dead sister Inga, and the Gestapo leave, apparently fooled. Fooled in part due to help from Captain K.

But the key point: Jojo has made his choice. He is now on Elsa’s side.

But there’s one last scene in the sequence. Adolf appears, only this time he’s no longer fun-and-games. He rants at Jojo, his rant sounding a little more like the Hitler of history. He gives a long speech, and it’s dark. It ends with: “To put it plainly – get your shit together and sort out your priorities. You’re ten, Jojo. Start acting like it.”

Jojo has almost entirely switched sides, and Adolf recognizes it and is fighting back. For the first time, an Adolf scene is not farcical.

In fact, this entire sequence is a mix of farce and drama. The Gestapo are ridiculous, but also deadly. And Adolf behaves like a spoiled child – he kicks a chair on his way out the door. But there’s blood and thunder behind his rant.

There’s another way in which the Adolf scene is pivotal. Although this is not mentioned in the screenplay, this is the last time that we see Jojo in his Nazi uniform. From now on, and with one brief exception that I’ll mention soon, he now dresses as a civilian. He has left the Nazi party for good. He’s made his choice.

Now just an aside. One thing I love about movies is that they use so many ways to tell stories. It’s not just the words, it’s not just the action, it’s not just the camera movement and lighting. It’s also things like costume, as we see here. Even makeup can be used to tell the story of a character’s journey. I love these multiple layers and ways of telling story.

Back to the movie. Jojo has just made his choice. And that choice has consequences. Because the next sequence is all about consequences. In the darkest moment of the movie, Jojo finds Rosie hanging dead in the town square. He has lost his mentor and is now alone.

Now clearly, this is not really because of anything Jojo did. Rosie was caught playing a dangerous game.

But in a story-logic sense, this is the price that Jojo has to pay for his transgression against the party. And he initially responds like a good Nazi: he blames a Jew. He comes back from Rosie to attack Elsa with his knife.

But he can’t bring himself to push the attack through. He nicks her, draws a little blood, but doesn’t really hurt her.

And the two have a moment where they reflect on Rosie, and where Elsa says that when she is free she will dance. Which is an important setup for the ending. And which is the end of this act.

There is nothing comic about this last sequence. It’s the most tragic, sequence in the film. No humor, no lightness. Just two kids dealing with a terrible loss. It’s a grim ending for act three.

Now we move into the final act, and the War comes to town. First there’s a montage that shows the passage of time. Jojo scrounges for food as he and Elsa live together.

There’s little humor in this montage, other than one scene of Adolf eating a unicorn head.

But the next sequence, the battle, is a tragicomic view of war. The entire town gears up for war, and they’re really not equipped for it. Old people and small children are handed weapons and go running into battle. It’s the height of absurdity and has some of the most absurd moments in the film, such as when Captain K appears in his gilded new uniform holding what looks like a blunderbuss.

There’s certainly farce here, but also tragedy underneath. People are acting ridiculous, but they’re also dying. It’s the perfect blending of the tones of this film.

At one point in this sequence, Fraulein Rahm thrusts Jojo into a soldier’s jacket. This almost gets Jojo killed when the Russians take him as a POW. But Captain K sacrifices himself, freeing Jojo.

Note that while Jojo wears a uniform here, it’s not his choice. Fraulein Rahm forced it on him. As, in fact, the Nazis have pretty much forced Jojo and the other children of Germany into being soldiers. And just as Jojo is almost destroyed by this act, so Germany was almost destroyed.

In any event, we now have one last sequence. Jojo encounters Yorki, and from something Yorki says, Jojo realizes that with the war over and lost, there is nothing to keep Elsa with him. So he goes home and first lies to Elsa. He tells her that Germany won the war. She’ll have to keep hiding. For just a moment, Jojo uses lies to try to keep her.

But then he encounters Adolf and finally rejects him. And then he brings Elsa outside where she sees that Germany lost the war. She is liberated. And after a moment where she hits him for lying to her, they dance and the movie ends.

So, like I said, four acts. A setup act. An act in which Jojo meets Elsa and goes from hating her as a Jew to starting to show empathy. An act in which Jojo comes to love Elsa, he protects her, and they unite in grief for his mother. And an act in which there’s a big battle and Jojo makes his final choice. He will be a good person. He is no longer a Nazi.

Which, of course, can be easily turned into three acts, with the midpoint being the moment when Jojo first shows empathy for Elsa. But again, I’ll continue fighting this battle, even if I’m the ridiculous soldier with the bright red cape.

Okay, let’s do a quick run-through Save the Cat. And the first thing to note: Jojo’s refusal to kill the rabbit is a save-the-cat moment. In spite of the fact that at this point he is a fanatic Nazi, his refusal to kill an innocent creature emphasizes his core decency. It makes us like him. If he had killed the cat, the movie would lose us.

Beyond that, most of the Save the Cat beats are here. The only one I don’t see is an explicit statement of the theme. But again, the theme is this movie is sufficiently clear that it doesn’t need one.

The other beats are present, and noted on a special lane in the Storylanes analysis. The all-is-lost and dark-night-of-the-soul are particularly prominent and tied to Rosie’s death and Jojo’s response to it.

The paired opening and closing moments are present, but are not explicit images. And the final image isn’t actually the last image in the movie.

In this case, the opening image is the first scene, where good-Nazi Jojo in his uniform shouts Heil Hitler to Adolf. And the corresponding final image is where Jojo finally confronts Adolf, telling him “Fuck Off, Hitler.” These map Jojo’s full journey from pro- to anti-Nazi.

Or you could argue that the last image of the movie, a closeup on Jojo as he happily dances with Elsa, is the true symbolic final image. It certainly pairs off well with the initial closeup of Jojo in the Nazi uniform. (Though that initial closeup isn’t the actual first shot of the film. But it’s the first one of consequence.)

For the other Save the Cat beats, check out the Storylanes analysis on Storylanes.com.

The Hero’s Journey also maps fairly well here. But there’s a couple of things to note about it.

First, Jojo has a call-to-adventure. He is called to the great adventure of being a German soldier fighting for the Nazi Party. But it’s a false call-to-adventure. This is not the adventure he should be on. And when he refuses to kill the rabbit, he refuses the call. He tries to get back to it when he throws the grenade, but that blows up on him.

It’s an interesting twist on the Call to Adventure and the Hero’s Journey. What should the hero do when called to the wrong adventure? In Jojo’s case, getting to the point of his final rejection of the Call is the whole point of the movie.

The other interesting twist on the Hero’s Journey is that Jojo has two dueling mentors. Adolf is his pro-Nazi mentor. But Rosie is his anti-Nazi mentor. The two, while never meeting, do battle for Jojo’s soul. I’ll talk more about that in a moment. But it is an interesting twist on the Hero’s Journey. What happens when you have two mentors, and they disagree? In this case, the entire movie is all about how that disagreement plays out.

Now let’s talk theme. And this is going to be an interesting and lengthy talk, and one that introduces a whole new model of story structure.

If you are interested in screenwriting, you may listen to the Scriptnotes Podcast. In fact, you probably should listen to the Scriptnotes Podcast. This is a podcast featuring John August and Craig Mazin, two top-level Hollywood screenwriters. Each has written many movies and TV shows. August most recently was screenwriter on Disney’s live-action Aladdin remake. Mazin just won an Emmy for writing the TV series Chernobyl.

As of this writing, they have produced 446 episodes of their podcast, which talks about a whole raft of issues about screenwriting. They cover everything from craft details to the business of screenwriting. If you want to learn more about screenwriting, I highly recommend it.

A few months back, Mazin produced an episode in which he lays out his theory of screenwriting, the approach he takes to writing a film. I strongly recommend it. There’s a link to it in the show notes on storylanes.com.

Now note: Mazin does not claim this is the one true way of structuring a film. Mazin and August are both in the anti-formula camp. But Mazin does say it’s a way he uses, and it can have value.

And while the other films we’ve covered in this podcast aren’t strong matches for the Mazin theory, JOJO RABBIT is. And so I’ve added a Storylanes lane talking about the Mazin method, and I’ll talk about it here as a way to discuss the theme of this movie.

And I should note that Mazin isn’t the only one with his approach. I’ve heard a lecture by Meg LeFauvre, the screenwriter who wrote the Pixar movie INSIDE OUT, about her approach. Boil things down and her method is pretty much the same as Mazin’s. But while Mazin presents a movie as a philosophical debate, LeFauvre sees it in more psychological and emotional terms. It’s a warmer presentation of the same idea, and depending on how your mind works, you may find LeFauvre’s approach more palatable. It’s certainly more touching – I found myself in tears when I heard her lecture on it.

You can find LeFauvre’s presentation of her approach in a video on the Sundance Collabs site. I’ll include a link to that in the show notes on storylanes.com.

I do recommend you listen to one or both of those presentations to get more detail on this approach. But I’ll present it as best I can through the lens of JOJO RABBIT. And while here I’ll mostly be using Mazin’s language, do note that LeFauvre’s approach is pretty much the same.

Basically, Mazin views the film as a debate between a thesis and antithesis. And the thesis is the film’s theme – the ultimate meaning and message of the movie. The antithesis is its opposite.

At the beginning of the movie, the protagonist believes in the antithesis. The movie charts the course of the protagonist’s journey from antithesis to thesis.

In JOJO RABBIT, the thesis can be expressed as, “Nazis are bad and empathy is good.” And so, of course, the antithesis is “It’s good to be a Nazi.”

The entire movie is a debate between these views as fought in the mind of Jojo. He comes in with a strong belief in the Nazi ideal. But slowly, over the course of the film, he changes his mind.

And, of course, Jojo has two mentors, and each represents one of the views. Adolf is, suitably, the spokesman for the pro-Nazi view. And Rosie, Jojo’s mom, represents the pro-empathy pro-love anti-Nazi position.

Mazin talks about how the film has to challenge the protagonist’s belief in the antithesis. We first see this in the Rabbit scene. Jojo’s belief is challenged when he’s called on to kill the rabbit. If he were a perfect Nazi, he’d just kill it. After all, the other Hitler Youth kids don’t seem to have any problems with the idea. But Jojo just can’t bring himself to do the killing. So he flees into the woods while the other kids shout taunts.

But then Adolf shows up. He helps Jojo justify not killing the rabbit. A rabbit has to be clever. It lives in a dangerous world. It lives by its wits. You can be a rabbit, sympathize with a rabbit, and still be a Nazi. So this challenge to Jojo’s worldview is fought off by a solid dose of rationalization provided by Adolf. Jojo won’t kill the rabbit – he’s too kind-hearted for that. But he still believes he can be a good Nazi without killing an innocent.

Then comes Elsa, and she provides a bigger challenge to Jojo’s worldview. And at first, Jojo sticks to his Nazi views. He treats her as his enemy to be defeated. Even when he reconciles to her presence, he tries to use her to learn more about the evil Jews. He won’t turn her in, but he still views her from a Nazi’s perspective, as something evil and different. It’s the same as with the rabbit: he can be a Nazi and still not be a ruthless killer.

But then we get to the midpoint. Jojo hurts Elsa, but he feels guilt. For the first time, Jojo feels for someone that his Nazi views tell him he should hate. It’s the first major crack in his pro-Nazi stance. Empathy has crept in, and his worldview is challenged.

The very next sequence is an extended debate between the thesis and antithesis carried out with the help of all of Jojo’s major influences. First comes Rosie, and she tells Jojo of the importance of love. He argues against her, but she clearly wins the point.

Next is a scene between Jojo and Elsa, and then Adolf has his turn. He says, “Now Jojo let me give you some really good advice. Once you see what’s in her mind and where she’s trying to get you to go – in your own head, you must go the other way. Don’t let her put you in a brain prison! That, dear Jojo, is one thing that cannot happen to a German! Do not let her boss your German brain around!” He’s talking about Elsa, but he could as easily be discussing Rosie.

Captain K and Yorki then have their moments, and neither seem to care much about the Jewish question.

But overall, this sequence is a clear argument between the pro- and anti-Nazi viewpoints. And it ends with Jojo deciding he loves Elsa. He’s gone beyond empathy.

Next, Jojo has to act on that empathy. He takes a stand when he helps keep the Gestapo from discovering who Elsa is. And Captain K, in helping Jojo cover up for Elsa, gives another model for the pro-empathy anti-Nazi viewpoint. Captain K pretends to be pro-Nazi, but he’s not, not really.

Of course, now Adolf gets angry at Jojo – the antithesis fights back hard. And there is a cost to Jojo’s action – Rosie is killed. But this also takes away Jojo’s pro-empathy mentor. From now on, he’s on his own.

And his first response to her death is a Nazi response. That’s his instinct: he’s not free of his old worldview yet. So he blames the Jew, tries to kill Elsa. But he can’t – by now he’s too far gone to the other side. And now he never again appears in a Nazi uniform – he’s rejected the Nazi view.

When Captain K saves Jojo he once again shows his true anti-Nazi colors. But once again, he does so with pro-Nazi camouflage. He pretends Jojo is a Jew, but only to help Jojo escape. And even though it costs Captain K his life, he has shown kindness and empathy.

Finally, Jojo faces his last test. He fears that Elsa, on learning that Germany lost the war, will leave him. So to stop this from happening, he lies to her, tells her Germany won. She’s in despair.

Now this is a very Nazi action on Jojo’s part. He’s resorting to a Big Lie in order to coerce someone else to do what he wants. It’s a reversion to the antithesis.

But on seeing how upset she is, he can’t keep it up. So he pretends to have found a way for her to escape.

He leaves her for a moment, and then Adolf makes his last appearance. This is his last desperate plea for the anthesis, for the Nazi view. It doesn’t go well for him.

ADOLF (CONT’D)

Now you listen to me. I’m going to give you one last chance to make things right. You’re going to put this on and forget about that disgusting Jewy cow up there, and you’re going to come back to me where you belong. Got it?

Jojo screws up the armband and throws it on the ground. Adolf buckles in pain.

ADOLF (CONT’D)

Heyyy… hey, how about you Heil me, yeah? Come on, for old times sake? (beat) Heil me, little man.

JOJO No…

ADOLF

Come on, you know you want to. Just a little Heil. Just a little little Heil for your old friend?

JOJO

No. Fuck off Hitler.

It’s Jojo’s final irrevocable rejection of Nazism, his final choice. And now he goes out and releases Elsa.

But note how Adolf acts this time. He’s pleading. He’s lost the argument, and he knows it. This isn’t the fun-loving Adolf of the start of the movie, the Adolf who knows Jojo is his guy. And this isn’t the Adolf who comes out near the end of Act Two, the blood and thunder Adolf who demands that Jojo toes the line. This is a whiny loser Adolf, one who even has a bullet hole in his head from his suicide. And one that Jojo definitively rejects.

Finally we have one last set of crucial signifiers of Jojo’s choice to live the empathetic life. First, when steeling himself to release Elsa, right before Adolf shows up for the last time, he looks in the mirror and says to himself: “Jojo Betzler. 10 and a half years old. Today… just do what you can.” This is important for two reasons. First, it mirrors his first line in the film: “Jojo Betzler. Ten years old. And today you join the ranks of the Jungvolk in a very special training weekend. It’s going to be intense. But today you become a man.”

But just as much, it reflects something his mother said to him, something she said when they first saw the bodies hanging in the town square.

ROSIE Look.

JOJO What did they do?

ROSIE (shrugs) What they could.

Now Jojo is the one doing what he can. Now Jojo has joined the resistance.

If that weren’t enough, when he leads Elsa out the door to freedom, there are more signifiers.

First, he ties the shoes Elsa’s wearing. Which happen to be an old pair of his mother’s shoes. But the fact that Jojo ties them is significant. To this point, he has not been able to tie shoes. Rosie was the one who tied the shoes. Now it’s Jojo. While Elsa is the one wearing Rosie’s shoes, Jojo is the one who steps into them.

Then there’s the last thing Jojo says to Elsa before going outside. It is:

ELSA Jojo, is it dangerous out there?

JOJO Extremely.

Rosie said the same thing to him, when he first left the house after his grenade wound.

JOJO Is it dangerous?

ROSIE Extremely.

Again, Jojo is acting the part of Rosie. He has taken over from his good mentor.

And note, Jojo says Extremely with a perfect wink, something he couldn’t do earlier in the film. A sign of his coming of age.

Finally, when they get outside and Elsa realizes she is safe, she and Jojo dance. Which is a callback to the moment, after Rosie died, when Elsa said that when she was free she’d dance. But is also a reference to Rosie, who spoke often about dancing and frequently danced herself.

So in the end, Jojo has taken over for Rosie. He dances like her. He ties shoes like her. He makes the same jokes she used to make. And he does what he can. He has become his mentor, and his choice is final.

I think this incredibly beautiful, quite well handled, and, if a little heavy-handed in the pure number of callbacks, all works rather nicely. And I wouldn’t lose a one of them.

So the thesis, or theme, has triumphed. Empathy wins out over Nazism. And Jojo has taken on the decent, loving, and kind-hearted aspects of his mother. Fade to black.

It’s incredibly satisfying. Well done, JOJO RABBIT.

And it follows the Mazin/LeFauvre approach. And it works quite well here.

Now let’s take a quick tour through the subplots. But since this is already running a little long, we’re going to make this fast. If you want more details, see the script analysis at storylanes.com.

I found a lot of subplots in this film. Some contributed to Jojo’s story, like Rosie’s story or the subplot of the Jew in the wall. Some reflected on it. Yorki’s arc, for example, serves as a model of the path Jojo’s life might have taken if he hadn’t blown himself up. And Captain K’s arc is mostly there because of the impact on Jojo’s arc. Captain K’s disillusionment with the Nazis and his inner decency make him a solid secret ally for Jojo.

One plot, the plot about Jojo’s book about Jews, a subplot that I call Yoohoo Jew for the name of the book, is largely a source of humor early on, as well as giving Jojo a reason to interact with Elsa after they are done fighting but before they become friends. But later, when the Gestapo arrive, the book distracts them, softening their menace by making them laugh. Thus, with humor, Yoohoo Jew serves a much-needed purpose and ends up saving Elsa’s life.

So these subplots do play a key part in the film. But I’m not going to go through them beat-by-beat. Again, if you want to see that, see the Storylanes analysis.

I will note one thing. Sometimes it’s hard to figure whether something is a subplot or just part of the main plot. Is the story of the Jew in the Wall a subplot? It feels a little like one – Elsa’s fate, though tied to Jojo, is still somewhat separate. You could imagine Elsa dying and Jojo surviving, or vice versa. But it’s still so central to what happens to Jojo that it’s hard to completely separate the two.

But I think that’s a good aspect of a subplot. A good subplot often influences the main story in some way. And it’s kind of cool when something that seems separate comes back in to be a key part of the main story.

Now a subplot doesn’t HAVE to influence the main story. Again, view Yorki’s arc here. That has almost no direct impact on Jojo.

But it is useful and adds to the film. It’s good to have something like that which we can use to triangulate on our protagonist. Yorki’s story does tell us something about Jojo, even if it does not directly influence him. And it’s evidence that there’s a world outside the film, which adds depth and richness.

So, we’re about through here. I don’t see any major flaws in this film. The scene of butterflies in Jojo’s stomach is a little odd: the animation doesn’t quite fit in with the style of the rest of the movie. Sure, the movie is over-the-top, but not to the point of animation. But I’m not going to make a big deal of that – it’s not a major flaw and doesn’t break the spell of this film for me.

One thing I would point out, that I don’t think is much of a flaw but some might, is that Jojo is often a somewhat passive protagonist. A lot of what happens to him is not a result of his choices. He doesn’t choose to find Elsa – it just sort of happens. Nothing he does causes Rosie’s death. That too just happens. And he does nothing in the final battle beyond hiding from it as best he can.

He does make choices in this film. But so much of what happens here just happens.

Is that a flaw? A lot of screenwriting gurus would argue that a protagonist should be active, that his choices should drive the action of the film. And while Jojo’s actions do drive some of the actions, they don’t drive most of them.

But given how much I love this movie, I’d have to say I don’t think it a flaw. And honestly, I’ve been having my doubts about opposition to a passive protagonist. I think a movie or story can work just fine with a certain passivity in the protagonist. That’s another argument, and probably a lengthy one. But suffice to say that I will add JOJO RABBIT to my stack of evidence supporting the idea that a somewhat passive protagonist can work.

And one last possible flaw, another that may not really be a flaw. It’s not really that brave these days to have a movie that concludes that it’s bad to be a Nazi. I mean, what’s the point in saying something that obvious?

Or at least, I might have said that, five years ago. Let’s just say that sometimes something that may seem obvious can acquire new relevance. So perhaps it’s always timely to remind people that empathy is a good thing. And that Nazis are bad.

Now let’s turn to screenwriter lessons. What are my three big takeaways from this movie?

First, I very much enjoyed encountering a film in the wild that so closely matched the Mazin/LeFauvre method. I liked the method on hearing of it. I like it even more having seen it play out so well in a movie that I so enjoyed. I’m going to try to use it in one of my own future projects, and seeing it at work here helped. I particularly liked the way that the thesis and antithesis were personified. That’s not necessary for the model, but as JOJO RABBIT shows, it helps.

Second, I really enjoy the way this movie subverts the Hero’s Journey. The Call to Adventure that should be resisted. The dueling mentors who battle over the soul of the protagonist. This isn’t the only movie with these things, but I rather like the way it handles them. Something to remember, and to consider in future projects.

Third, this movie reinforces something I’ve been gradually coming to, and that’s when making a movie, subtlety be damned. I used to really like movies that were subtle in their messaging, that expected a lot from audiences in understanding what was going on. As a result, I made several shorts that just confused my audience.

I had already moved away from that theory, but JOJO RABBIT pushes me even farther in that direction. This is not a subtle movie. Just look at Jojo’s final resolution of his thematic dilemma. He has a scene near the end that’s a near parallel to the first scene, only this time he denies his support for Nazism instead of affirming it. He kicks Adolf in the nuts and shouts, “FUCK OFF, HITLER.” He ties Elsa’s shoes, shoes that were originally his mother’s. He uses his mother’s language when bringing Elsa to the outside world. And the movie ends with Elsa and Jojo dancing, a direct callback to his mother. None of this is at all subtle. You’d have to be sleeping through the end to miss its significance. And that’s okay.

So subtlety be damned. There’s nothing wrong with being a little heavy-handed.

And a special bonus takeaway: I love love love the way this movie mixes tone. I’m working on a project where the tone shifts radically from Mel Brooks-style sex farce to heart-searing tragedy. I find it reassuring to see a film like JOJO RABBIT pull off those kinds of shifts. And incredibly educational to see how it does it. I’m about to do a revision of my script: you can bet I’ll have JOJO RABBIT in mind when I do.

So that’s JOJO RABBIT. A great mix of tone, with both great farce, deep tragedy, and incredibly sweet moments. I really do love this movie, and analyzing it has only made me love it more.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this episode as much as I did, and learned as much from listening as I did from preparing it. And always, if you want to dive a little deeper into my thinking on this film, you can find the analysis at Storylanes.com. You’ll also find the script of this episode there, if you’re happier with reading a podcast than listening to it. All other episodes are there as well.

Next time, we’re going to dive into TV-land and do the pilot for BREAKING BAD. This is generally considered one of the best TV pilots ever, and it should be interesting to see how it plays out when looked at through a Storylanes lens.

Until then, this is Joe Dzikiewicz and the Storylanes podcast. Talk at you later!