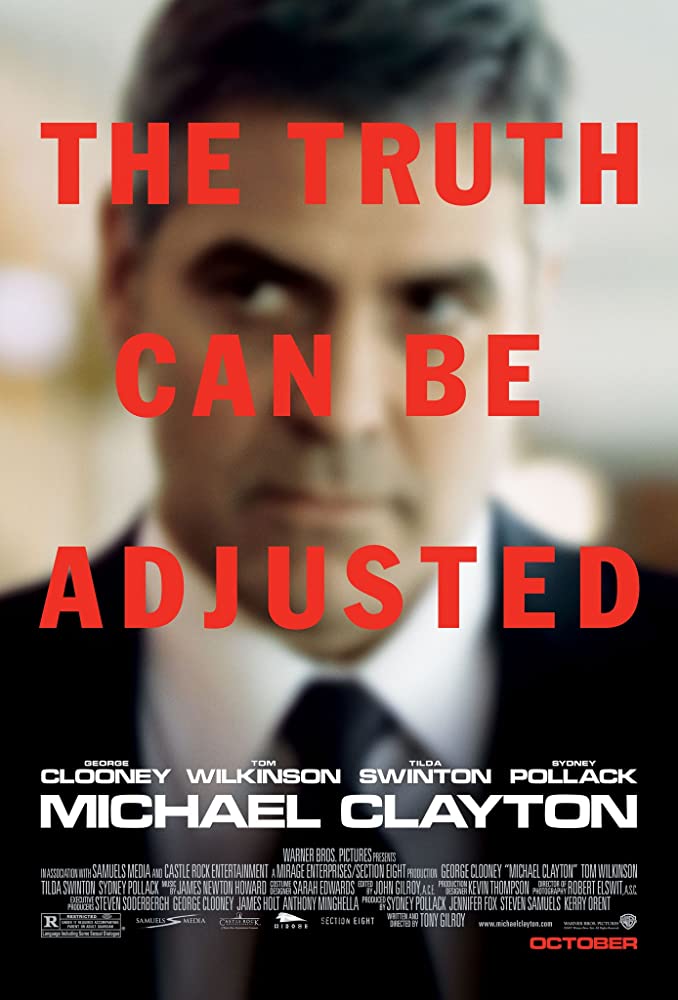

This week, we stay with Michael Clayton and do a deep-dive analysis into two scenes from that terrific movie. This will be something a little different.

Links:

And here is the script of this episode:

Hi, I’m Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where every episode we do a deep dive into a movie or TV show. And to go along with this analysis, I publish a chart of the story we’re covering on the storylanes.com website, a chart I produced while preparing the episode. You don’t need to look at that chart – the podcast is standalone. But if you’re interested in diving a little deeper, check it out at storylanes.com.

Today we’re doing something a little different. Instead of doing a deep dive into the structure of a screenplay, I’m going to dive into two scenes of the film we covered last week, MICHAEL CLAYTON. In particular, I’m going to look at the midpoint scene, where Michael confronts Arthur in an alley and, in the midst of a whole lot of great dramatic conflict, tells him something that causes Arthur to drive the plot off in a whole other direction. And I’m also going to look at the scene a few minutes later when Karen orders Arthur’s murder. They are both superbly written, and it’s my hope that we’ll learn something about dialogue and the crafting of a scene by looking at these.

But as usual, this podcast assumes you’ve seen the movie. There will be spoilers. And there won’t be detailed explanations of plot points. So if you listen to this without knowing the movie, you’re out of luck: the movie will be spoiled for you, and you may not understand what I’m talking about. It’s basically the worst of all worlds.

And there’s another layer of spoilers for this one. I recommend you go back and listen to the last episode, where I cover the entire film, before listening to this one. You’ll get my views of the structure of the entire script, and an understanding of where these scenes fit in that context.

So let’s dive right into the first scene that we’re going to analyze. It’s the midpoint scene, the confrontation between Michael and Arthur.

To set this up: Arthur is a senior lawyer at the firm where Michael is a fixer. And Arthur is the problem that Michael has to fix: he has gone off the reservation and is doing things that make his bosses suspect he’s working against the interests of the client in a big product liability case. And this is, in fact, true: Arthur is trying to help one of the plaintiffs in that suit, because Arthur knows his client is in the wrong. Totally and completely in the wrong. Like, evil-wrong.

But Arthur has a major problem: he is bipolar, off his meds, and deeply manic. This is causing him to act out in ways like stripping off his clothes in the middle of a deposition. Michael has been brought in by his firm to fix this problem. But he’s lost track of where Arthur is.

And that brings us to this scene, where Michael is driving around trying to find Arthur. I’ll start by playing the entire scene.

(Note: for the reader, the scene starts on page 69 and goes to page 73 of the script.)

So that’s a little more than four minutes. And this scene is a major turning point: after learning his phone is tapped, Arthur directly challenges his client, and that drives the rest of the film.

Let’s take a look at the detailed structure of this scene. And to do so, I’ve broken it down into beats. I’ve done a Storylanes chart of this scene, identifying the beats of the scene. You can find a link to it at Storylanes.com.

I find this scene breaks down into seven distinct beats. Each beat captures one key part of the scene and includes some major shift in the relationships in the scene. This includes both the relationship between Michael and Arthur, but also includes the relationship between them and the world around them. Let’s step through those beats.

First, there is a prolog. Michael drives around, looking for Arthur, with his son in the car. There’s a little dialog between Michael and his son Henry, but the scene is mostly driven by visuals.

Here it is:

INT. THE MERCEDES — DAY (CONT)

MICHAEL driving. Scanning. HENRY’s patience has thinned.

HENRY

If we’re not gonna get to the movies why don’t you just say so. (beat) I want to go home.

MICHAEL Hang on, Henry —

(something they just passed–)

MICHAEL whips the car to the curb —

MICHAEL (already jumping out–)

— stay right here — lock the doors — I’ll be right back — don’t move! –

There’s a couple of things this beat does. It establishes that Michael is searching for Arthur. And it paints a poor picture of Michael as a father: he is not giving Henry proper attention, instead focusing on his work problem. That both shows Michael in a bad light and establishes how important finding Arthur is to him – he even places it above spending time with his son. And to add the finishing touch, Michael leaves ten-year-old Henry alone in the car in a rough neighborhood – notice the “lock the doors.”

But now he’s spotted Arthur, and we’re on to the next beat.

EXT. ALLEY — DAY (CONT)

ARTHUR walking away.

MICHAEL (jogging after him) Arthur! Arthur! Wait up!

ARTHUR stops. Turns. Caught. In his arms he’s cradling twenty-five fresh baguettes.

ARTHUR Whoaa… (almost losing his loaves–) Michael. Jesus. You scared me.

MICHAEL Making a delivery?

ARTHUR No… (smiling) Very funny. Nothing like that… (as if it were all completely natural and needed no further explanation–) Have one…go on…really… (offering) It’s still warm. Best bread I’ve ever had in my life.

MICHAEL suddenly holding warm French bread.

So I think of this as initial pleasantries. On the surface, it’s two old friends greeting each other.

But underneath there’s a heavy subtext: Michael is angry at Arthur for running out on him, and Arthur just wants to be left alone. But the two haven’t really joined in conflict. Instead, Michael is making smalltalk, though admittedly smalltalk with an edge, and Arthur is responding in kind.

But that starts to change in the next beat, which goes like this.

MICHAEL So welcome home.

ARTHUR I know. The hotel. I’m sorry. I was getting a little overwhelmed.

MICHAEL But you’re feeling better now?

ARTHUR Yes. Definitely. Much better.

MICHAEL Just not enough to call me back.

ARTHUR hesitant. Straining to keep the mania down.

ARTHUR I wanted to organize my thoughts. Before I called. That’s what I’ve been doing.

MICHAEL And how’s that going?

ARTHUR Good. Very good. I just… (fighting the flood) I need to be more precise. That’s my goal.

MICHAEL

As good as this feels, you know where it goes.

ARTHUR

No. You’re wrong. What feels so good is not knowing where it goes.

Notice how gradually we’re getting down to business here. Michael is pushing harder. But it starts out as pure subtext: the “So welcome home” could be sincere, but in the context Michael is complaining about Arthur running away from him in Milwaukee. And Arthur responds to that subtext by making excuses for his running.

But the subtext keeps bubbling closer and closer to the surface, and Michael keeps escalating the conflict by letting it get more direct. He goes from, “So welcome home,” to “Just not enough to call me back” to “As good as this feels, you know where it goes.” Each time, he gets more and more direct. And each time, Arthur parries as best as he can.

I think the key point in this beat is when Arthur says, “What feels so good is not knowing where it goes.” That line does a couple of things. First, Michael believes Arthur is denying his mental illness, which sets off Michael into the anger of the next scene. But in a way, it’s a warning from Arthur: Arthur doesn’t know how this will end, because he’s never done anything like this before. This isn’t just him giving into his mental illness: it’s Arthur trying to redeem himself by doing the right thing in this case. And he doesn’t know where that will go.

But Michael has now lost his patience. That leads to the next part, where Michael lectures Arthur like he might a child. This includes Michael’s longest blocks of dialogue, and it goes like this:

MICHAEL

How do I talk to you, Arthur? So you hear me? Like a child? Like a nut? Like everything’s fine? What’s the secret? Because I need you to hear me.

ARTHUR I hear everything.

MICHAEL

Then hear this: You need help. Before this gets too far, you need help. You’ve got great cards here. You keep your clothes on, you can pretty much do any goddamn thing you want. You want out? You’re out. You wanna bake bread? Go with God. There’s one wrong answer in the whole pile and there you are with your arms around it.

ARTHUR I said I was sorry.

MICHAEL

You thought the hotel was overwhelming? You keep pissing on this case, they’re gonna cut you off at the knees.

ARTHUR

I don’t know what you’re talking about.

MICHAEL

I’m out there trying to cover for you! I’m telling people everything’s fine, you’re gonna be fine, everything’s cool. I’m out there running this Price- Of-Genius speech for anybody who’ll listen and I get up this morning and I find out you’re calling this girl in Wisconsin and you’re messing with documents and God knows what else and –

Here Michael is totally in charge. He brings it to Arthur, and Arthur can only give short responses. Not only short responses, but Arthur responds from a powerless place. He’s acting like a teenager caught breaking curfew. “I said I’m sorry.”

But at the end of this beat, Michael reveals that he knows that Arthur is calling Anna, the girl in Wisconsin. And that triggers Arthur. Because now Arthur knows someone is tapping his phones. And so we move to the next beat.

ARTHUR How can you know that?

MICHAEL

— they’ll take everything — your partnership, the equity —

ARTHUR

How do you know who I call?

MICHAEL

— they’ll pull your license!

ARTHUR

HOW DO YOU KNOW I CALLED ANNA?

MICHAEL

From Marty! You’re denying it?

ARTHUR How does he know?

MICHAEL I don’t know. I don’t give a shit.

ARTHUR stepping back. Flushed. Paranoia rising.

ARTHUR You’re tapping my phones.

MICHAEL (it’s to weep) Jesus, Arthur…

ARTHUR Explain it! Explain how Marty knows.

So Arthur starts to snap back. His paranoia is at full throttle, but we the audience know he’s right: they really are tapping his phones. Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

Things are shifting, though Michael doesn’t seem to know it yet. Michael’s still trying to strongarm Arthur, trying to get him under control. And so we go into the next section, where Michael tries to reassert control, go back into lecturing mode:

MICHAEL

You chased this girl through a parking lot with your dick hanging out! You don’t think she got off the phone with you and speed-dialed her lawyer?

ARTHUR

She wouldn’t do that. I know that.

MICHAEL

Really. You think your judgment is state-of-the-art right now? (before he can step away) They’re putting everything on the table here. You need to stop and think this through. I will help you think this through. I will find someone to help you think his through. Don’t do this. You’re gonna make it easy for them.

Michael is once more the lecturing parent. But Arthur is no longer the defensive teenager. He’s fighting back. Now he responds, “She wouldn’t do that. I know that.” Michael’s approach no longer works with Arthur in this new place.

And so Arthur gathers up his strength, and for the first time in this scene, possibly the first time in the film, we see Arthur as he is beneath the mental illness: a man with great power and command of the law. He is now the one who lectures, and with one speech he destroys Michael’s position.

ARTHUR I have great affection for you, Michael, and you lead a very rich and interesting life, but you’re a bagman not an attorney. If your intention was to have me committed, you should’ve kept me in Wisconsin where the arrest record, videotape, and eyewitness accounts of my inappropriate behavior had jurisdictional relevance. I have no criminal record in the State of New York and the crucial determining criteria for involuntary commitment is danger: “Is the defendant a danger to himself or others.” You think you’ve got the horses for that? Good luck and God bless. But I’ll tell you this, the last place you want to see me is in court.

Arthur is now completely in command. And he moves from the formal speech of a skilled attorney to a colloquial smackdown. You can hear that transition in these two sentences: “I have no criminal record in the State of New York and the crucial determining criteria for involuntary commitment is danger: “Is the defendant a danger to himself or others.” You think you’ve got the horses for that?”

And note also the reference to horses. This is after the scene in the teaser, when Michael communed with horses.

Now Michael has his response, and now he’s the one who whines like a teenager.

MICHAEL I’m not the enemy.

ARTHUR Then who are you?

Michael’s destroyed, and Arthur responds with his challenge. And that challenge is a doozy. It’s the key question of the movie, and Michael spends the rest of the film finding his answer.

This is a powerful scene that lays the path for the rest of the film.

But notice a few other craft things about this.

First, note who speaks the most in each beat. Early on, Arthur talks the most, but that’s because he’s babbling. He speaks from a place of weakness, while Michael just shoots out short sentences, little jabs to get Arthur’s attention.

Then comes the section where Michael lectures Arthur. And here he is totally in control, doing most of the talking. Arthur’s reduced to defensive one-liners.

But then Arthur gets angry. And the two speak pretty much the same amount.

There’s a short beat where Michael starts lecturing again. But Arthur is no longer defensive: he now fights back.

And then Arthur gives his lecture, and he smacks Michael down. We see the power that Arthur has, and Michael can’t stand up to it.

One last beat, where Michael tries to get back in. But Arthur quickly shuts him down.

And the scene is over.

Note how the power shifts in this scene. Note the key turning point, when Arthur realizes someone is tapping his phone. And note: that is at almost exactly two minutes into this four minute scene. It’s the midpoint of the midpoint, where the entire scene pivots.

It’s all a solid structure.

We can also take a look at it in terms of some scene analysis methods. Now our usual models don’t apply here, but there are others specifically about scenes.

The main one I’d like to use is Aaron Sorkin’s approach. In Sorkin’s model, in every scene each character has an intention, an obstacle, and a strategy to overcome the obstacle.

In this scene, Michael’s intention is to get Arthur to stop misbehaving, to get his mental illness under control, and to stop causing problems for the firm. His obstacle is Arthur: Arthur’s stubbornness, Arthur’s unwillingness to play along. And his strategy is to find Arthur and talk him into behaving. To try to reason with him, but also to threaten him. But also, Michael is starting to lose his temper here, and that’s another obstacle for him.

By contrast, Arthur is the more interesting character in this scene. His intention is to get away. His obstacle is Michael. But he keeps shifting his strategy. At first, he tries to disarm Michael by talking about bread and other distractions. When that doesn’t work, he gets defensive, tries to just put his head down.

But then, when he learns that his phone is tapped, he goes on the attack. And now he dresses down Michael, gives him the straight scoop.

This works. Michael is reduced to defensiveness. And so when Arthur leaves, Michael does nothing to try to stop him. Arthur has achieved his intention, but Michael has failed at his. And the screenplay references this in the last line of description in the scene, where it describes how we last see Michael: “Standing on the sidewalk with a baguette in his hand and a great variety of failures arranging themselves around his heart.”

Intention, obstacle, and strategy. It’s a good way of looking at this scene.

So much for that scene. Let’s take a look at another.

This is the scene a little later in the film when Karen orders Arthur’s murder. It starts on page 76 of the screenplay and it goes something like this.

(See page 76 of the screenplay for this scene.)

Now, there’s a few things interesting to note about this scene.

First, it’s only two and a half minutes. So not long at all.

Second, there aren’t really distinct beats in this scene. There’s no shift of power – Karen holds the power throughout the scene, everything is her decision to make.

Once she hears the recording, Karen has one goal in this scene: to order Verne to kill Arthur. But to do so without being too overt about it. Her goal doesn’t change, and at the end she’s accomplished it.

Verne has only one goal: to get his orders for what to do next. Again, his goal doesn’t change and he accomplishes it.

So what makes this scene stand out?

I love the way Gilroy uses the wording in this scene, the way he has Karen ordering Arthur’s death without explicitly ordering Arthur’s death. Note all the ways she asks for it:

“You have to contain this.”

“What’s the option for something along these lines?”

“That there’s a more limited option,”

“Something I’m not thinking of.”

“And the other way?”

In all of these cases, she is asking to have Arthur murdered. But she, smart lawyer that she is, is not going to be explicit with that request. That’s well done.

And notice, even at the end, she doesn’t answer Verne’s question: “You mean okay you understand, or okay proceed?”

Finally, one note: in the screenplay, the scene ends with Verne asking if she wants to bring Don in on it, and Karen saying no. In the filmed version, they move that dialogue up and end it on Verne’s question about whether to proceed. I think that’s a much stronger ending of the scene: it leaves it on the key question.

Anyway, I don’t have a huge amount to say about that scene. But I did want a chance to include it as I think it is so well written.

But it is worth looking at it through Sorkin’s model. Karen’s intention is to order Arthur’s murder. Her obstacle is her own unwillingness to order it directly, to maintain for herself some kind of plausible deniability. Her strategy is to talk around the request until Verne understands what she wants. And she accomplishes that when she says, “And the other way?”

Verne’s intention is to get his orders from Karen. His obstacle is her obfuscation and unwillingness to be clear. His strategy is to keep talking until he understands.

Both achieve their intentions in this scene.

Now, let’s step back and take a closer look at the dialogue.

I must admit: these scenes confound some of my theories. Of late, when writing dialogue I look at the rhythm of the line. In particular, when all else fails and I don’t have a reason to do otherwise, I will often try to make my lines iambic. And for those of you who forgot your high school English, Iambic is a rhythm in which you alternate stressed and unstressed syllables. So, for example, you take this line:

The cat runs to the other side of the room.

That is not iambic. But if you change it like this:

The cat will run across the room,

Suddenly it’s iambic. Listen to the stresses in the syllables:

The Cat will Run aCross the Room.

You can hear how it flows better. It’s beneath conscious notice, but the words definitely have a rhythm that is lacking in the first version.

Now a lot of famous movie lines are iambic or its cousin, trochaic:

We’re gonna need a bigger boat.

May the Force be With you.

Round up the usual suspects.

ET Phone Home.

So when I looked at the dialogue here, I was expecting it to be iambic.

To my surprise, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Some lines are, but that seems to be almost by accident. I doubt that Tony Gilroy set out to use iambic in this dialogue.

Though I can’t help but notice that the final couplet of the first scene we covered is iambic:

MICHAEL I’m not the enemy.

ARTHUR Then who are you?

For that matter, both the key lines and the final lines in the other scene are mostly iambic.

KAREN And the other way?

VERNE Is the other way.

Note the rhythm. “AND the Other WAY IS the Other WAY.”

VERNE You mean okay, you understand? Or okay, proceed?

“You MEAN oKAY you UNderSTAND? Or oKAY proCEED?”

So Gilroy trots out the use of rhythm in key lines, but not throughout. He doesn’t overdo it, but he uses it when it packs a punch. And a lesson for me, if not for all screenwriters: iambic and other rhythms can be useful, and I think the examples that I’ve given show that they are. But they are not the end-all and be-all of writing dialogue and should not be overused. Once again, the central lesson of this podcast comes through: there is no single one-size-fits-all solution to writing, just a large toolbox of different methods that can be applied in different circumstances.

So, what are the lessons from these scenes?

First, a scene can be shaped according to the shifts of power between the characters in the scene. This is a powerful way of doing things, and it can lead to a terrific dramatic scene, as shown in the first scene we examined.

But as we saw in the second scene, it’s not necessary. Power never shifts in that second scene, but it still works.

Second, you can control power dynamics in a scene by controlling who is doing the talking. This isn’t always the case, but sometimes having one person talk more shows that person is dominant. Or even, depending on how its used, can be used to show the other person is dominant: being strong and silent when the other person is babbling does make a statement. The midpoint scene shows examples of both of this: at first, Arthur does most of the talking from a position of weakness. Then Michael takes over, from a position of strength. Finally Arthur becomes the primary speaker as he gives the longest speech in the scene, but now he’s doing it from a position of total control.

So it can be done both ways, but you really should carefully consider who is talking the most and how that plays into the dynamics of the scene.

Third, no single rule controls everything. That’s even true of rules that I like, like iambic rhythms. After all, even Shakespeare would abandon iambic speech at times. Any “rule” that anyone will tell you about screenwriting is useful in some contexts, less useful in others. The key is to have a well-stocked intellectual toolbox so that you always have the right tool for the problem at hand.

And that’s MICHAEL CLAYTON, round two. Next time we’ll move onto something else. We’re going to do JENNIFER’S BODY, which is, I should stress, not the same quality of most of the films we’ve covered. But it has some similarities to a project that I’m working on, and so I want to do a deep-dive into it. And because I’m doing a deep-dive, so will this podcast.

I hope you found this week’s episode both entertaining and educational. For more information about it, check us out at Storylanes.com.

And do give us a review on your podcast service, it will help others find us. I see we have two reviews on Apple Podcasts, so thanks to Froggy the Gremlin and the unnamed other reviewer – I appreciate it.

This is Joe Dzikiewicz and the Storylanes podcast. Talk at you later.